Le Fort Fractures: Classification, Clinical Features, and Management

Medi Study Go

Related Resources

Comprehensive Guide to Maxillofacial Fractures in Oral Surgery

Classification of Midfacial Fractures: Systems and Exam Tips

Zygomatic Complex Fractures: Diagnosis and Surgical Approaches

Gillies Temporal Approach in Zygomatic Arch Fractures

Orbital Blowout Fractures: Pathophysiology and Treatment Protocols

Mandibular Fractures: Classification Systems and Clinical Relevance

Champy's Lines of Osteosynthesis: Principles and Application

Mandibular Angle Fractures: Diagnosis, Complications, and Surgical Management

Condylar Fractures of the Mandible: Types, Indications for Surgery, and Outcomes

Basic Principles of Fracture Fixation in Maxillofacial Surgery

Dental Wiring Techniques in Maxillofacial Fracture Management

CSF Rhinorrhea in Maxillofacial Trauma: Causes, Diagnosis, and Management

Epistaxis Associated with Facial Fractures: Emergency Management

Complications of Maxillofacial Fractures: Early and Late Sequelae

Key Takeaways

- Le Fort fractures follow predictable anatomical weakness patterns, with Le Fort I being the most common in clinical practice

- The classic triad of malocclusion, facial elongation, and mobility distinguishes Le Fort fractures from other midface injuries

- CT imaging with multiplanar reconstructions is essential for accurate classification and surgical planning

- Modern treatment emphasizes rigid internal fixation with miniplates rather than prolonged intermaxillary fixation

- Early surgical intervention within 7-14 days optimizes functional and aesthetic outcomes

Introduction

Le Fort fractures represent a specific subset of maxillary fractures that follow predictable lines of weakness through the midface. First described by French military surgeon René Le Fort in 1901 through cadaveric experiments, these fracture patterns continue to serve as the foundation for understanding midface trauma. While pure Le Fort patterns are uncommon in modern clinical practice, understanding these classic descriptions remains crucial for proper diagnosis and treatment planning.

The significance of Le Fort fractures extends beyond their anatomical classification. These injuries often result from high-energy impacts and are frequently associated with other facial fractures, cranial injuries, and systemic trauma. The complex anatomy involved requires comprehensive understanding of the relationships between the maxilla, nasal bones, orbital walls, and skull base.

Modern management of Le Fort fractures has evolved significantly from Le Fort's original observations. Contemporary treatment emphasizes three-dimensional restoration of facial anatomy, stable internal fixation, and early return to function. This approach has dramatically improved outcomes compared to historical methods relying on prolonged immobilization and external support.

The classification system, while over a century old, remains clinically relevant because it describes the biomechanical behavior of the midface under stress. Understanding these patterns helps surgeons predict associated injuries, plan surgical approaches, and anticipate potential complications. The three classic patterns represent increasing severity of injury and corresponding complexity of treatment.

Table of Contents

- Historical Background and Anatomical Basis

- Le Fort Classification System

- Clinical Presentation and Diagnosis

- Imaging and Radiographic Features

- Treatment Principles and Surgical Management

- Complications and Outcomes

Historical Background and Anatomical Basis

Le Fort's Original Work

René Le Fort's groundbreaking work involved dropping cannonballs onto cadaveric heads from various heights to study fracture patterns. His systematic approach identified three consistent patterns of maxillary separation that corresponded to lines of structural weakness in the facial skeleton. These experiments laid the foundation for understanding midface biomechanics and trauma patterns.

The anatomical basis for Le Fort fractures lies in the architectural design of the midface, which consists of vertical buttresses connected by horizontal supports. The areas between these buttresses represent relative weak points where fractures tend to propagate under stress. Le Fort's classification essentially describes the three most common pathways of fracture propagation.

Modern Understanding of Midface Anatomy

Contemporary understanding of midface anatomy has expanded Le Fort's original concepts. The facial skeleton functions as an integrated framework where forces are distributed through predictable pathways. The pterygoid plates, often overlooked in simplified descriptions, play a crucial role in Le Fort fractures and must be carefully evaluated during treatment planning.

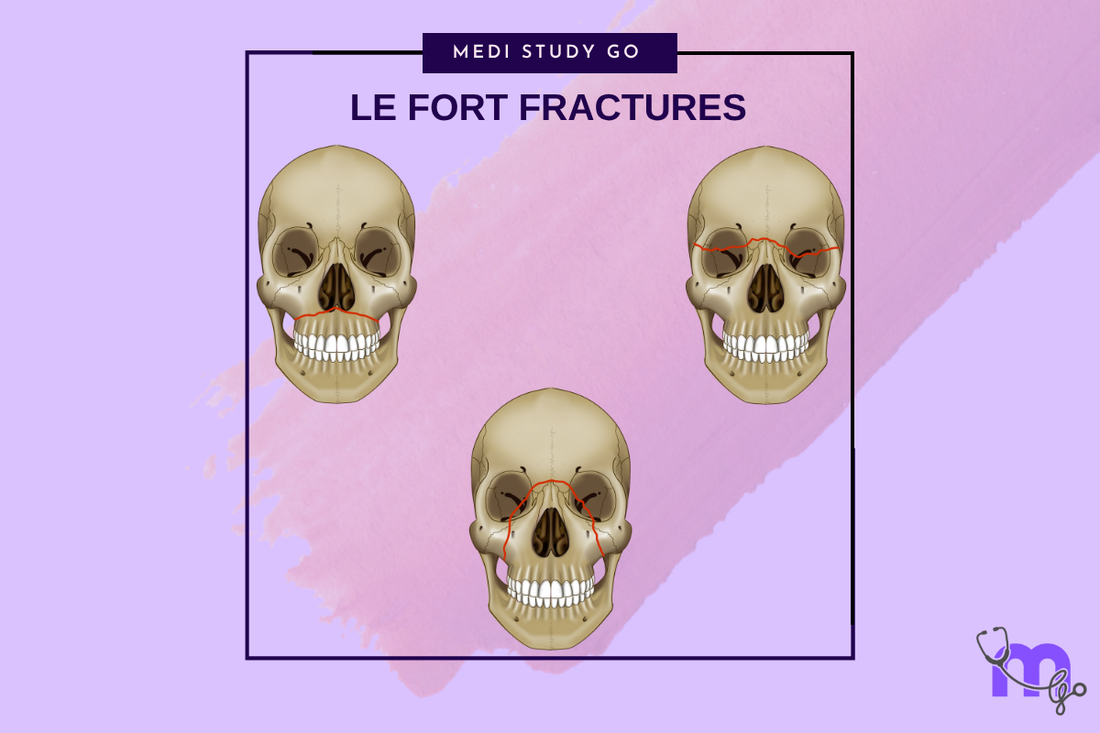

The relationship between the maxilla and surrounding structures creates the characteristic features of each Le Fort pattern. Le Fort I fractures separate the dentoalveolar segment, Le Fort II fractures create a pyramidal fragment, and Le Fort III fractures completely separate the midface from the cranial base. These patterns reflect the progressive involvement of stronger structural elements as impact energy increases.

Le Fort Classification System

Le Fort I (Horizontal Maxillary Fracture)

Le Fort I fractures, also known as Guerin fractures, represent horizontal separation of the dentoalveolar segment from the rest of the maxilla. The fracture line typically passes through the piriform aperture, across the maxillary sinus walls, and through the pterygoid plates at their junction with the maxilla.

This pattern results from direct horizontal impact to the upper jaw or alveolar process. The fracture separates the teeth-bearing portion of the maxilla, which may become mobile as a single unit. Clinically, patients present with malocclusion, mobility of the maxillary teeth, and characteristic bruising of the hard palate known as Guerin's sign.

The fracture line in Le Fort I injuries typically remains below the level of the nasal floor and maxillary sinus roof. This preservation of the sinus cavity distinguishes Le Fort I from more extensive patterns. However, bleeding into the maxillary sinus is common and may be evident on imaging studies.

Le Fort II (Pyramidal Fracture)

Le Fort II fractures create a pyramidal-shaped fragment with the nasal bones forming the apex and the maxillary alveolar process forming the base. The fracture line extends from the nasal bones through the medial orbital walls, crosses the inferior orbital rims, and passes through the anterior walls of the maxillary sinuses before continuing to the pterygoid plates.

This pattern typically results from impact to the central midface, such as striking the nasal bridge or central maxilla. The pyramidal fragment includes the nasal bones, portions of the maxilla, and parts of the orbital floors. Patients often present with a characteristic "dish-face" deformity due to posterior displacement of the central midface.

What distinguishes Le Fort III from other midface fractures?

Le Fort III fractures represent complete craniofacial dysjunction, separating the entire midface from the cranial base. The fracture line passes through the nasofrontal sutures, across the medial and lateral orbital walls, through the zygomatic arches or zygomaticofrontal sutures, and continues to the pterygoid plates. This pattern results from severe high-energy impacts and is often associated with other significant injuries.

The distinguishing feature of Le Fort III fractures is the complete mobility of the midface as a single unit when grasped and manipulated. This "floating face" appearance is pathognomonic for Le Fort III injuries. Patients typically present with severe facial elongation, telecanthus, and often have associated neurological injuries due to the proximity to the skull base.

Marciani's Modifications

Modern clinical practice recognizes that pure Le Fort patterns are uncommon, leading to development of modified classification systems. Marciani's modification adds subtypes that account for associated nasal fractures and naso-orbito-ethmoid injuries commonly seen with Le Fort II and III patterns.

These modifications better reflect clinical reality and provide more precise guidance for treatment planning. For example, Le Fort IIa includes associated nasal fractures, while Le Fort IIb involves naso-orbito-ethmoid fractures. Similar subtypes exist for Le Fort III patterns, recognizing the frequent occurrence of combination injuries.

Clinical Presentation and Diagnosis

Physical Examination Findings

The clinical presentation of Le Fort fractures varies depending on the specific pattern and associated injuries. However, certain common features help distinguish these injuries from other facial fractures. The classic triad includes malocclusion, facial elongation, and abnormal mobility of maxillary segments.

Inspection may reveal facial asymmetry, periorbital ecchymosis, subconjunctival hemorrhage, and nasal deformity. Palpation often identifies step defects along fracture lines, particularly at the infraorbital rims and frontonasal region. The presence of cerebrospinal fluid rhinorrhea suggests skull base involvement and requires immediate attention.

How is maxillary mobility assessed in Le Fort fractures?

Maxillary mobility assessment requires gentle bimanual palpation with one hand stabilizing the frontal bone and the other grasping the maxillary teeth or alveolar process. In Le Fort I fractures, only the dentoalveolar segment moves. Le Fort II fractures demonstrate movement of the central pyramidal fragment, while Le Fort III fractures show mobility of the entire midface.

The examiner should assess movement in all planes: anteroposterior, mediolateral, and vertical. The pattern of mobility helps distinguish between fracture types and guides treatment planning. However, examination should be gentle to avoid further displacement or injury to surrounding structures.

Care must be taken to avoid excessive manipulation, particularly in suspected Le Fort III fractures where skull base injuries may be present. The examination should be systematic and documented carefully to guide subsequent treatment decisions.

Associated Injuries and Complications

Le Fort fractures are frequently associated with other injuries due to the high-energy mechanisms typically involved. Cranial injuries, including skull base fractures and intracranial hemorrhage, occur in approximately 20-30% of cases. Ophthalmologic injuries, including globe rupture and visual disturbances, require immediate evaluation.

Airway compromise may result from bleeding, edema, or displacement of fractured segments. Early assessment and management of airway patency is crucial, particularly in Le Fort III fractures where severe facial swelling and bleeding can rapidly compromise breathing.

Imaging and Radiographic Features

Computed Tomography Evaluation

CT imaging has revolutionized the diagnosis and treatment planning for Le Fort fractures. Multiplanar imaging with fine-cut sections allows precise visualization of fracture lines, displacement patterns, and associated injuries. Three-dimensional reconstructions facilitate surgical planning and patient counseling.

The key radiographic findings vary by fracture pattern but include discontinuity of the pterygoid plates in all Le Fort fractures. Le Fort I fractures show separation at the piriform aperture and lateral nasal walls. Le Fort II fractures demonstrate involvement of the medial orbital walls and inferior orbital rims. Le Fort III fractures show fractures at the nasofrontal and zygomaticofrontal sutures.

Diagnostic Imaging Protocols

Standard imaging protocols for suspected Le Fort fractures include axial, coronal, and sagittal CT images with both bone and soft tissue windows. Special attention should be paid to the pterygoid plates, orbital contents, and skull base structures. Vascular imaging may be indicated in high-energy injuries with suspected vascular involvement.

The McGrigor-Campbell lines provide a systematic approach to evaluating Waters radiographs for midface fractures. These imaginary lines help identify disruptions in normal anatomical continuity and guide further evaluation with CT imaging.

Treatment Principles and Surgical Management

Timing of Intervention

Optimal timing for Le Fort fracture repair typically falls within 7-14 days post-injury, allowing initial swelling to subside while preventing significant scar tissue formation. Earlier intervention may be necessary for airway compromise, persistent bleeding, or globe injuries. Delayed treatment beyond 3 weeks may require osteotomies and bone grafting.

The decision regarding timing must balance multiple factors including associated injuries, patient stability, soft tissue condition, and surgeon availability. In polytrauma patients, maxillofacial injuries are often managed after life-threatening conditions are stabilized.

Surgical Approaches and Reduction Techniques

Modern surgical approaches for Le Fort fractures emphasize adequate exposure while minimizing visible scarring. Common approaches include maxillary vestibular incisions for Le Fort I fractures, combined intraoral and extraoral incisions for Le Fort II, and extensive exposure through coronal and intraoral incisions for Le Fort III.

Reduction techniques vary by fracture pattern but generally follow the principle of restoring facial height, width, and projection in that sequence. Establishment of proper occlusion is crucial and may require intermaxillary fixation during the reduction process. Rowe's disimpaction forceps and Hayton-Williams forceps are commonly used instruments for fracture reduction.

What fixation methods are preferred for Le Fort fractures?

Modern fixation methods for Le Fort fractures favor rigid internal fixation with titanium miniplates and screws over prolonged intermaxillary fixation. Le Fort I fractures typically require fixation at the nasomaxillary and zygomaticomaxillary buttresses using 2.0mm miniplates.

Le Fort II fractures require four-point fixation at the nasofrontal region, inferior orbital rims, and zygomaticomaxillary buttresses. Le Fort III fractures need more extensive fixation, often requiring five or six points including the frontonasal area, frontozygomatic sutures, and zygomatic arches.

The choice of plate thickness and screw length depends on bone quality and fracture stability. Monocortical screws are typically adequate for facial bone fixation, while bicortical fixation may be necessary in severely comminuted fractures or osteoporotic bone.

Complications and Outcomes

Early Complications

Early complications of Le Fort fractures include hemorrhage, infection, nerve injury, and dental complications. Massive bleeding may require arterial ligation or embolization, particularly involving the sphenopalatine or maxillary arteries. Infection risk is elevated in open fractures and requires appropriate antibiotic coverage.

Nerve injuries commonly affect the infraorbital nerve in Le Fort II fractures and may result in permanent numbness of the midface. Dental complications include tooth avulsion, crown fractures, and pulpal necrosis requiring endodontic treatment.

Late Complications and Secondary Reconstruction

Late complications include malunion, chronic pain, enophthalmos, and aesthetic deformities. Malunion often results from inadequate reduction or loss of fixation and may require secondary osteotomies and repositioning. Enophthalmos may develop from inadequate restoration of orbital volume or post-traumatic fibrosis.

Secondary reconstruction may be necessary for persistent functional or aesthetic problems. This typically involves careful analysis of the deformity, surgical planning with imaging studies, and often requires bone grafting or osteotomies to achieve optimal results.

Long-term Outcomes

Long-term outcomes for Le Fort fractures are generally favorable when treated appropriately. Most patients achieve satisfactory facial appearance and function, though some degree of residual numbness or minor asymmetry is common. Functional outcomes including mastication and speech are typically good with proper occlusal restoration.

Regular follow-up is important for detecting late complications and ensuring optimal healing. Patient satisfaction is generally high when realistic expectations are established and comprehensive treatment is provided.

Conclusion

Le Fort fractures represent a significant subset of maxillofacial trauma requiring specialized knowledge and surgical expertise. While the classic classification system developed over a century ago continues to provide valuable insights, modern practice recognizes the complexity and variability of these injuries.

Contemporary management emphasizes comprehensive evaluation, appropriate timing of intervention, and stable internal fixation to achieve optimal functional and aesthetic outcomes. Understanding the anatomical basis and biomechanical principles underlying these fractures is essential for successful treatment.

The evolution of imaging technology and surgical techniques has significantly improved outcomes for patients with Le Fort fractures. However, the fundamental principles of anatomic reduction, stable fixation, and attention to functional restoration remain central to successful management.

Future developments in three-dimensional imaging, computer-assisted surgery, and regenerative techniques will likely further improve outcomes. Nevertheless, the careful clinical assessment and surgical judgment required for these complex injuries will continue to be essential components of optimal care.