Classification of Midfacial Fractures: Systems and Exam Tips

Medi Study Go

Related Resources

Comprehensive Guide to Maxillofacial Fractures in Oral Surgery

Le Fort Fractures: Classification, Clinical Features, and Management

Zygomatic Complex Fractures: Diagnosis and Surgical Approaches

Gillies Temporal Approach in Zygomatic Arch Fractures

Orbital Blowout Fractures: Pathophysiology and Treatment Protocols

Mandibular Fractures: Classification Systems and Clinical Relevance

Champy's Lines of Osteosynthesis: Principles and Application

Mandibular Angle Fractures: Diagnosis, Complications, and Surgical Management

Condylar Fractures of the Mandible: Types, Indications for Surgery, and Outcomes

Basic Principles of Fracture Fixation in Maxillofacial Surgery

Dental Wiring Techniques in Maxillofacial Fracture Management

CSF Rhinorrhea in Maxillofacial Trauma: Causes, Diagnosis, and Management

Epistaxis Associated with Facial Fractures: Emergency Management

Complications of Maxillofacial Fractures: Early and Late Sequelae

Key Takeaways

- Multiple classification systems exist for midfacial fractures, each serving different clinical and academic purposes

- Le Fort classification remains the gold standard but must be understood alongside modern modifications

- Functional classifications like Rowe and Williams better guide treatment decisions than purely anatomical systems

- High-yield exam concepts include fracture favorability, associated injury patterns, and treatment implications

- Understanding classification rationale enhances clinical decision-making beyond memorization

Introduction

Classification systems for midfacial fractures serve as the foundation for clinical communication, treatment planning, and academic assessment in maxillofacial surgery. While these systems may appear as mere memorization exercises, understanding their development, clinical relevance, and practical applications is crucial for both examination success and clinical competence.

The complexity of midfacial anatomy has necessitated multiple classification approaches, each emphasizing different aspects of fracture patterns, treatment requirements, or prognostic factors. From Le Fort's century-old anatomical descriptions to contemporary functional classifications, each system provides unique insights into fracture behavior and management strategies.

For examination purposes, candidates must not only memorize classification details but also understand the clinical reasoning behind each system. Board examiners frequently test the ability to apply classification knowledge to clinical scenarios, requiring integration of anatomical knowledge, biomechanical principles, and treatment considerations.

Modern clinical practice increasingly emphasizes functional outcomes over purely anatomical descriptions. However, traditional classification systems remain relevant because they describe predictable injury patterns and associated complications. Understanding both historical and contemporary approaches provides comprehensive knowledge essential for clinical practice.

This comprehensive review examines major classification systems for midfacial fractures, emphasizing high-yield concepts for examinations while providing practical insights for clinical application. The focus extends beyond memorization to understanding the rationale and clinical implications of each classification approach.

Table of Contents

- Historical Development of Classification Systems

- Le Fort Classification: Foundation and Modifications

- Contemporary Functional Classifications

- Specialty-Specific Classification Systems

- High-Yield Exam Concepts and Clinical Pearls

- Integration and Clinical Application

Historical Development of Classification Systems

Evolution of Fracture Classification

The development of midfacial fracture classification parallels advances in understanding facial anatomy and biomechanics. Early classifications were primarily descriptive, focusing on anatomical location and appearance. The transition to mechanistic classifications reflected growing understanding of force transmission and fracture propagation patterns.

Le Fort's work in 1901 established the foundation for systematic fracture classification by identifying predictable patterns of midface separation. His experimental approach using cadaveric specimens created the first scientific basis for understanding midfacial fracture patterns. This work remained largely unchanged for decades due to its fundamental accuracy in describing fracture behavior under stress.

Limitations of Early Systems

Traditional classification systems, while foundational, had significant limitations in clinical practice. Pure Le Fort patterns occur in less than 20% of clinical cases, with most patients presenting combination injuries or unilateral patterns. This discrepancy between classic descriptions and clinical reality necessitated development of modified and contemporary systems.

The emphasis on anatomical description rather than functional implications limited the clinical utility of early systems. Treatment planning requires understanding of functional deficits, reconstruction requirements, and prognostic factors that purely anatomical classifications fail to address adequately.

Le Fort Classification: Foundation and Modifications

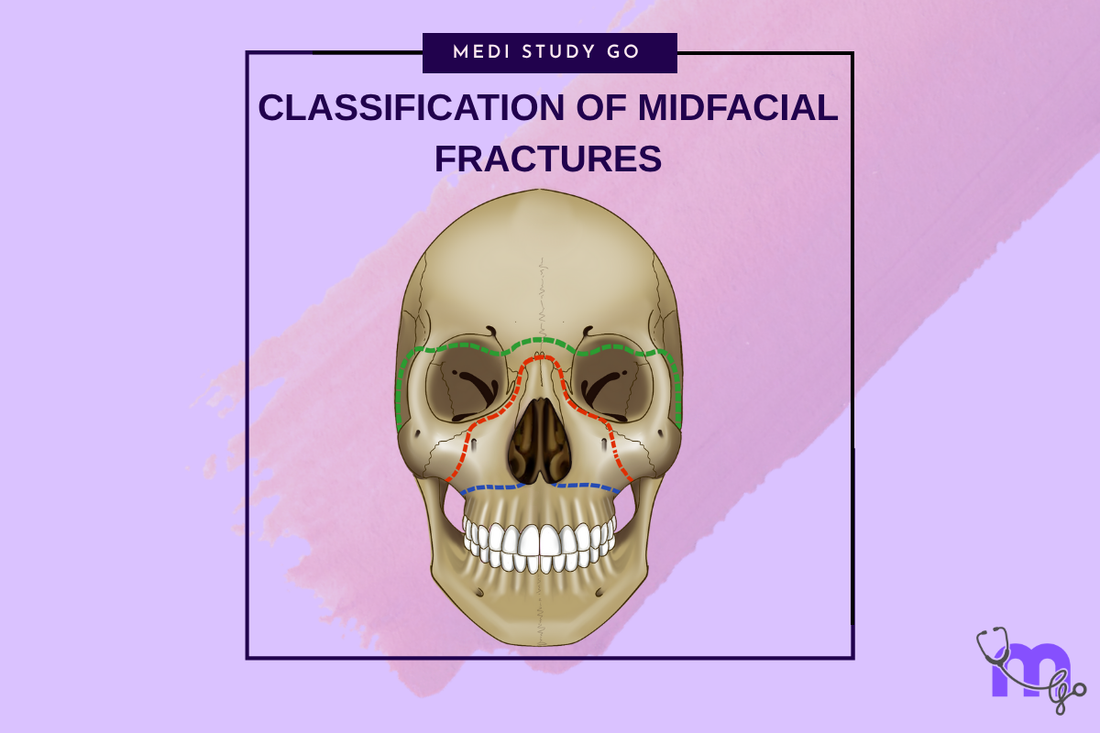

Classic Le Fort Patterns

The Le Fort classification describes three horizontal fracture patterns through the midface, each representing increasing severity and complexity. Le Fort I (horizontal maxillary fracture) separates the dentoalveolar segment, Le Fort II (pyramidal fracture) involves the central midface, and Le Fort III (craniofacial dysjunction) completely separates the midface from the cranium.

Understanding the anatomical pathways of each pattern remains crucial for examination purposes. Le Fort I fractures pass through the piriform aperture, maxillary sinus walls, and pterygoid plates at their junction with the maxilla. Le Fort II fractures extend through the nasal bones, medial orbital walls, inferior orbital rims, and continue to the pterygoid plates. Le Fort III fractures involve the nasofrontal sutures, orbital walls, zygomatic arches, and pterygoid plates.

Which anatomical structures are consistently involved in all Le Fort fractures?

The pterygoid plates are the only anatomical structures consistently fractured in all Le Fort patterns, making them pathognomonic for maxillary fractures. This consistent involvement reflects the mechanical role of the pterygoid plates as the final pathway for force transmission from the maxilla to the skull base.

Recognition of pterygoid plate fractures on imaging studies confirms maxillary involvement and helps distinguish Le Fort fractures from other midfacial injuries. The pattern of pterygoid involvement may also indicate the severity and extent of associated injuries.

Marciani's Modifications (1993)

Marciani's modification of the Le Fort classification adds subtypes that recognize commonly associated injuries. These modifications include nasal fractures (IIa, IIIa), naso-orbito-ethmoid fractures (IIb, IIIb), and cranial base extensions (IVa, IVb, IVc). This system better reflects clinical reality while maintaining the utility of the original classification.

The practical value of Marciani's system lies in its recognition of injury combinations that require coordinated treatment approaches. For example, Le Fort IIb fractures involving NOE injuries require specialized techniques for medial canthal reconstruction that pure Le Fort II fractures do not.

Contemporary Functional Classifications

Rowe and Williams Classification

The Rowe and Williams classification divides midfacial fractures into those involving dental occlusion and those that do not. This functional approach recognizes that fractures affecting dental function require different treatment strategies than those involving only the upper facial skeleton.

Fractures involving occlusion include dentoalveolar injuries and subzygomatic Le Fort patterns (I and II). These require careful attention to dental relationships and often benefit from intermaxillary fixation during treatment. Fractures not involving occlusion include suprazygomatic injuries (Le Fort III) and isolated upper facial fractures that can be managed without consideration of dental relationships.

Erich's Directional Classification

Erich's classification categorizes midfacial fractures based on the direction of the fracture line: horizontal, pyramidal, and transverse patterns. This system emphasizes the mechanical aspects of fracture propagation and provides insights into the forces responsible for injury patterns.

The directional approach helps predict associated injuries and complications. Horizontal fractures tend to involve dental structures, pyramidal fractures affect nasal and orbital function, and transverse fractures often involve cranial base structures with potential neurological implications.

What factors determine fracture favorability in midfacial injuries?

Fracture favorability in midfacial injuries depends on the relationship between fracture line orientation and muscle force vectors. Favorable fractures have lines of fracture that resist displacement by muscle pull, while unfavorable fractures tend toward displacement despite fixation.

The concept applies particularly to zygomatic and maxillary fractures where masseter and pterygoid muscle forces can displace inadequately reduced fragments. Understanding favorability helps predict fracture stability and guides fixation strategies during treatment planning.

Specialty-Specific Classification Systems

Ophthalmologic Classifications

Orbital fracture classifications focus on visual function and anatomical restoration requirements. The distinction between pure blowout fractures (isolated orbital wall fractures) and impure fractures (combined wall and rim involvement) has important implications for surgical approach and timing.

Manson's classification considers impact energy and comminution degree, helping predict surgical complexity and visual outcomes. This system recognizes that high-energy injuries often require more extensive reconstruction and have higher complication rates.

Neurosurgical Considerations

From a neurosurgical perspective, midfacial fractures are classified based on their relationship to the cranial base and potential for intracranial extension. Le Fort III and NOE fractures have the highest association with skull base injuries and cerebrospinal fluid leaks.

The classification of frontonasal injuries considers both aesthetic and functional implications, including potential for anosmia, epiphora, and telecanthus. These considerations influence treatment timing and approach selection.

High-Yield Exam Concepts and Clinical Pearls

Board Examination Favorites

Examination questions frequently focus on pattern recognition, associated injury prediction, and treatment implications rather than simple memorization. High-yield concepts include the relationship between fracture patterns and mechanism of injury, complications specific to each fracture type, and indications for surgical versus conservative management.

Key examination topics include the "floating face" sign in Le Fort III fractures, Guerin's sign in Le Fort I injuries, and the significance of cerebrospinal fluid rhinorrhea in upper facial fractures. Understanding these clinical signs and their implications demonstrates practical knowledge beyond classification memorization.

Clinical Decision-Making Points

Critical decision points in midfacial fracture management include timing of intervention, surgical approach selection, and fixation method choice. Classifications guide these decisions by providing prognostic information and treatment recommendations based on fracture pattern and severity.

The concept of the "golden period" for fracture repair (typically 7-14 days post-injury) applies differently to various fracture types. Understanding these timing considerations and their relationship to fracture classification is essential for optimal patient management.

Common Examination Pitfalls

Students often focus excessively on memorizing classification details while neglecting clinical applications. Successful examination performance requires understanding the reasoning behind classifications and their practical implications. Common errors include confusing unilateral and bilateral patterns, misunderstanding fracture favorability concepts, and inadequate consideration of associated injuries.

Another frequent pitfall involves applying pure classification patterns to complex clinical scenarios. Real patients rarely present with textbook patterns, requiring integration of multiple classification concepts and clinical judgment for optimal management.

Integration and Clinical Application

Multi-System Approach

Contemporary practice requires integration of multiple classification systems to fully characterize complex injuries. A single patient may have fractures best described by different classification systems, requiring synthesis of anatomical, functional, and specialty-specific considerations.

For example, a patient with a unilateral Le Fort II fracture and associated orbital blowout may require application of Le Fort classification for the maxillary component, orbital fracture classification for the visual considerations, and functional classification for treatment planning decisions.

Treatment Planning Integration

Effective treatment planning requires translation of classification information into actionable treatment decisions. This includes surgical approach selection, fixation method choice, and coordination of multidisciplinary care when indicated.

Understanding classification systems enhances communication between specialists and provides a framework for treatment sequencing in complex cases. The ability to translate classification concepts into practical treatment plans demonstrates advanced clinical understanding.

Quality Assurance and Outcomes

Classification systems provide standardized terminology for outcomes research and quality improvement initiatives. Consistent classification use enables comparison of treatment approaches and identification of best practices for specific injury patterns.

Long-term outcomes studies rely on accurate classification to identify factors associated with successful treatment and complications. This research continues to refine classification systems and treatment recommendations.

Conclusion

Classification systems for midfacial fractures serve multiple purposes beyond academic requirements, providing frameworks for clinical decision-making, research, and quality improvement. While memorization of classification details remains important for examinations, understanding the rationale and clinical applications ensures competent practice.

The evolution from purely anatomical to functional classifications reflects growing understanding of patient care requirements and treatment outcomes. Modern practitioners must be familiar with multiple systems and their appropriate applications to different clinical scenarios.

Successful examination performance requires integration of classification knowledge with clinical reasoning skills. Understanding why classifications exist and how they guide treatment decisions demonstrates the advanced knowledge expected of maxillofacial surgery specialists.

Future developments in imaging technology and treatment techniques will likely lead to further refinement of classification systems. However, the fundamental principles of systematic injury description and treatment guidance will remain central to optimal patient care.

The mastery of classification systems represents a foundation for advanced clinical practice rather than an end goal. Continuous integration of new knowledge and clinical experience builds upon this foundation to achieve optimal patient outcomes.