Epistaxis Associated with Facial Fractures: Emergency Management

Medi Study Go

Related Resources

Comprehensive Guide to Maxillofacial Fractures in Oral Surgery

Le Fort Fractures: Classification, Clinical Features, and Management

Classification of Midfacial Fractures: Systems and Exam Tips

Zygomatic Complex Fractures: Diagnosis and Surgical Approaches

Gillies Temporal Approach in Zygomatic Arch Fractures

Orbital Blowout Fractures: Pathophysiology and Treatment Protocols

Mandibular Fractures: Classification Systems and Clinical Relevance

Champy's Lines of Osteosynthesis: Principles and Application

Mandibular Angle Fractures: Diagnosis, Complications, and Surgical Management

Condylar Fractures of the Mandible: Types, Indications for Surgery, and Outcomes

Basic Principles of Fracture Fixation in Maxillofacial Surgery

Dental Wiring Techniques in Maxillofacial Fracture Management

CSF Rhinorrhea in Maxillofacial Trauma: Causes, Diagnosis, and Management

Complications of Maxillofacial Fractures: Early and Late Sequelae

Key Takeaways

- Epistaxis in facial fractures can be life-threatening and requires immediate assessment and intervention

- Nasal packing remains the first-line treatment for most traumatic epistaxis cases

- Arterial ligation or embolization may be necessary for refractory bleeding

- Understanding vascular anatomy is crucial for effective bleeding control

- Early intervention prevents complications and reduces morbidity

Introduction

Epistaxis represents one of the most challenging immediate complications associated with facial fractures, potentially leading to life-threatening hemorrhage if not promptly and effectively managed. The rich vascular supply of the nasal cavity and adjacent structures creates significant bleeding potential when disrupted by traumatic injury.

The management of epistaxis in the setting of facial fractures requires understanding of nasal and maxillofacial vascular anatomy, bleeding control techniques, and advanced surgical interventions. The urgency of hemorrhage control must be balanced with appropriate assessment and treatment of associated injuries.

Emergency management protocols emphasize rapid assessment, immediate bleeding control, and systematic approach to treatment escalation when initial measures prove inadequate. Understanding these protocols and maintaining proficiency in bleeding control techniques is essential for all practitioners involved in facial trauma care.

Anatomy and Blood Supply

Nasal Vascular Anatomy

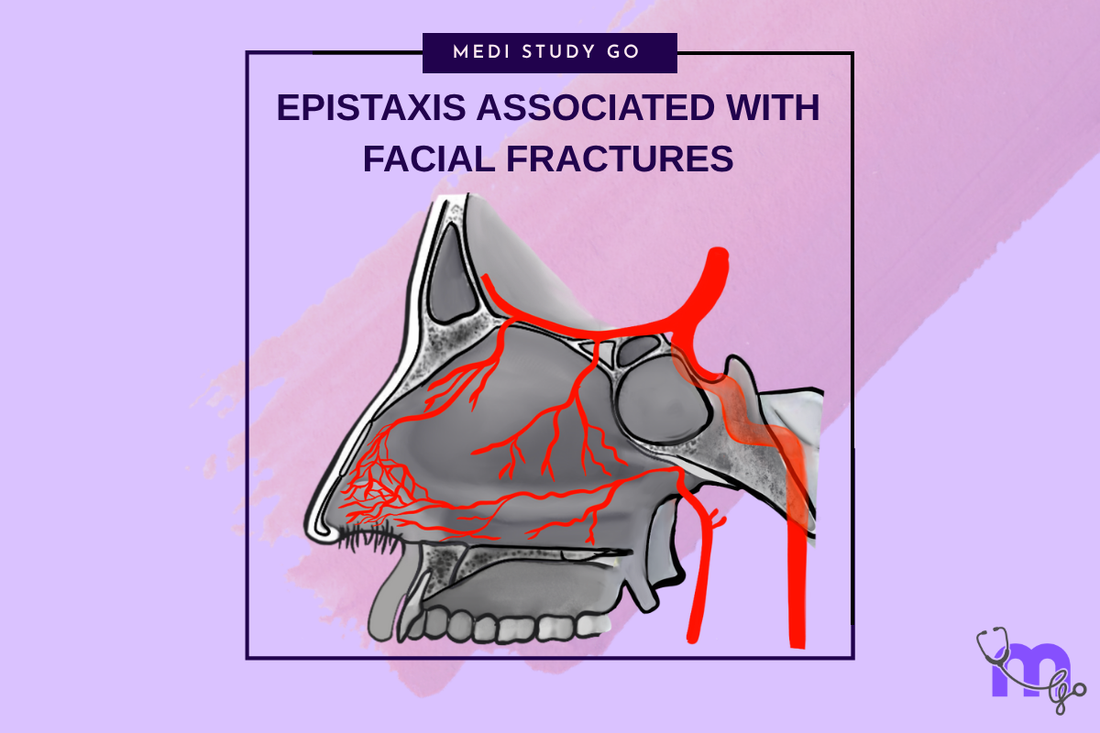

The nasal cavity receives blood supply from both the external and internal carotid artery systems, creating extensive vascular networks that are vulnerable to traumatic injury. The sphenopalatine artery, a terminal branch of the maxillary artery, provides the primary blood supply to the posterior nasal cavity.

The anterior nasal cavity receives supply from the anterior ethmoidal arteries and branches of the facial artery. The convergence of multiple vascular territories in Kiesselbach's area (anteroinferior nasal septum) creates a particularly vulnerable region for bleeding.

Fracture-Related Vascular Injury

Facial fractures can cause epistaxis through direct vessel injury, disruption of supporting bone structures, or displacement of nasal anatomy. Le Fort fractures commonly involve the maxillary and sphenopalatine arteries, potentially causing severe bleeding.

Nasal bone fractures may damage anterior ethmoidal vessels, while naso-orbito-ethmoid fractures can involve the anterior and posterior ethmoidal arteries. Understanding these injury patterns helps predict bleeding sources and guide treatment approaches.

What makes epistaxis particularly dangerous in pediatric facial trauma patients?

Pediatric patients have smaller blood volumes, making significant epistaxis more rapidly life-threatening. A child's total blood volume is approximately 80 mL/kg, so even moderate bleeding can lead to hemodynamic instability more quickly than in adults.

Additionally, children may be less able to communicate symptoms and may swallow blood, masking the true extent of hemorrhage. The smaller nasal anatomy also makes packing and surgical interventions more technically challenging.

Clinical Assessment and Initial Management

Primary Survey and Hemodynamic Assessment

Initial assessment follows standard trauma protocols, beginning with airway, breathing, and circulation evaluation. Massive epistaxis can compromise the airway through blood aspiration or anatomical distortion from facial fractures.

Hemodynamic status assessment includes vital signs, mental status, and evidence of shock. Rapid estimation of blood loss guides the urgency of intervention and need for resuscitation measures.

Bleeding Localization

Determining the source of bleeding guides treatment selection and predicts intervention requirements. Anterior bleeding typically originates from Kiesselbach's area and may be controlled with simple measures, while posterior bleeding often requires more aggressive intervention.

The pattern of bleeding, associated fractures, and response to initial measures help localize the bleeding source. Endoscopic examination may be necessary when adequate visualization cannot be achieved through simple inspection.

Emergency Bleeding Control

Immediate bleeding control measures include direct pressure, head elevation, and topical vasoconstrictors when available. These simple measures may provide temporary control while more definitive treatments are prepared.

Nasal packing represents the primary emergency intervention for most cases of traumatic epistaxis. Understanding proper packing techniques and materials is essential for effective bleeding control.

Nasal Packing Techniques

Anterior Nasal Packing

Anterior nasal packing controls bleeding from the anterior nasal cavity and is effective for most epistaxis cases associated with nasal fractures. Various materials are available, including petroleum-impregnated gauze, expandable nasal tampons, and specialized nasal balloons.

Proper technique involves systematic packing of the entire nasal cavity with adequate pressure to compress bleeding vessels while avoiding excessive trauma to surrounding tissues. The packing should be placed in layers from posterior to anterior for optimal effectiveness.

Posterior Nasal Packing

Posterior nasal packing may be necessary for bleeding originating from the sphenopalatine artery or other posterior sources. This technique is more complex and uncomfortable for patients but may be essential for controlling life-threatening hemorrhage.

Traditional posterior packing uses folded gauze or specially designed posterior packs that are positioned in the nasopharynx and secured with anterior packing. Balloon catheter systems provide an alternative approach that may be easier to place and more comfortable for patients.

How long should nasal packing remain in place for traumatic epistaxis?

Nasal packing for traumatic epistaxis should typically remain in place for 48-72 hours to allow adequate hemostasis and initial healing. Shorter periods may result in rebleeding, while longer periods increase the risk of complications such as infection and tissue necrosis.

The duration may be adjusted based on bleeding severity, patient factors, and response to treatment. Close monitoring during the packing period is essential to detect complications and assess treatment effectiveness.

Advanced Interventions

Endoscopic Management

Endoscopic techniques allow direct visualization of bleeding sources and precise application of hemostatic measures. Cautery, clip application, and selective vessel ligation can be performed under endoscopic guidance with superior precision compared to blind techniques.

Endoscopic management requires specialized equipment and training but offers advantages of precise bleeding control with minimal tissue trauma. This approach is particularly valuable for posterior bleeding sources that are difficult to access with traditional methods.

Arterial Ligation

Surgical ligation of feeding vessels may be necessary for refractory epistaxis that fails to respond to packing and endoscopic measures. The sphenopalatine artery is the most commonly ligated vessel, accessed through a sublabial or endoscopic approach.

External carotid artery ligation represents a more aggressive approach reserved for life-threatening hemorrhage when other measures have failed. This procedure carries significant morbidity and should only be performed by experienced surgeons.

Angiographic Embolization

Interventional radiology techniques allow selective embolization of bleeding vessels with minimal morbidity compared to surgical ligation. This approach is particularly valuable for posterior bleeding sources and patients who are poor surgical candidates.

Embolization success rates exceed 90% for traumatic epistaxis, making it an attractive option for refractory cases. However, the technique requires specialized equipment and expertise that may not be immediately available in all settings.

Specific Fracture Patterns

Le Fort Fracture Bleeding

Le Fort fractures commonly involve the maxillary artery and its branches, potentially causing severe epistaxis. The fracture pattern disrupts normal vascular anatomy and may create multiple bleeding sources requiring comprehensive management.

Treatment often requires a combination of packing, surgical exploration, and vessel ligation. Understanding the vascular anatomy involved in different Le Fort patterns guides treatment planning and intervention selection.

Nasal Fracture Hemorrhage

Simple nasal fractures typically cause anterior epistaxis that responds well to conservative measures and anterior packing. However, complex or comminuted fractures may involve multiple vessel territories requiring more aggressive intervention.

Associated septal hematoma should be identified and treated promptly to prevent complications such as septal perforation or abscess formation. Drainage of septal hematomas may be necessary in addition to bleeding control measures.

NOE Fracture Bleeding

Naso-orbito-ethmoid fractures can involve the anterior and posterior ethmoidal arteries, creating bleeding that may be difficult to control with simple packing. These fractures often require surgical exploration and direct vessel control.

The complex anatomy involved in NOE fractures may require combined approaches including endoscopic visualization and external surgical access. Coordination between maxillofacial and neurosurgical teams may be necessary for optimal management.

Complications and Management

Immediate Complications

Immediate complications of epistaxis include airway compromise, aspiration, and hemodynamic instability. Prompt recognition and treatment of these complications are essential for preventing morbidity and mortality.

Airway management may require suction, positioning, or advanced airway techniques depending on bleeding severity and patient condition. Hemodynamic support with fluid resuscitation and blood products may be necessary for significant blood loss.

Packing-Related Complications

Nasal packing can cause complications including sinusitis, septal perforation, and tissue necrosis. Proper packing technique and appropriate duration minimize complication risks while maintaining treatment effectiveness.

Toxic shock syndrome represents a rare but serious complication associated with prolonged nasal packing. Understanding risk factors and maintaining appropriate antibiotic prophylaxis helps prevent this potentially fatal complication.

Long-term Sequelae

Long-term complications of traumatic epistaxis may include anosmia, chronic rhinitis, and nasal deformity. These complications may result from the initial injury, treatment interventions, or both.

Follow-up care should include assessment for persistent symptoms and functional deficits that may require additional treatment. Early recognition and treatment of complications optimize long-term outcomes.

Special Populations

Anticoagulated Patients

Patients taking anticoagulant medications present particular challenges in epistaxis management due to impaired hemostasis. Treatment may require reversal of anticoagulation in addition to standard bleeding control measures.

The risks and benefits of anticoagulation reversal must be carefully weighed, considering the indication for anticoagulation and bleeding severity. Consultation with appropriate specialists guides decision-making in complex cases.

Elderly Patients

Elderly patients may have increased bleeding risk due to medication use, comorbidities, and age-related vascular changes. These factors may require modification of standard treatment approaches and more aggressive intervention.

The increased fragility of nasal tissues in elderly patients requires gentle packing techniques and careful monitoring for complications. Lower thresholds for advanced interventions may be appropriate in this population.

Prevention and Quality Improvement

Trauma Prevention

Primary prevention focuses on injury prevention through safety education, protective equipment use, and environmental modifications. Understanding common injury mechanisms guides prevention strategies and public health initiatives.

Secondary prevention involves early recognition and treatment of epistaxis to prevent progression to severe hemorrhage. Training healthcare providers in bleeding control techniques improves outcomes and reduces complications.

Protocol Development

Standardized protocols for epistaxis management ensure consistent, evidence-based care while reducing treatment delays. These protocols should address assessment, initial management, escalation criteria, and specialist consultation guidelines.

Regular protocol review and update based on current evidence and institutional experience optimizes patient care and outcomes. Quality improvement initiatives help identify areas for improvement and monitor treatment effectiveness.

Conclusion

Epistaxis associated with facial fractures represents a potentially life-threatening emergency requiring prompt recognition and effective management. Understanding vascular anatomy, bleeding control techniques, and escalation strategies is essential for optimal patient care.

The key to successful management lies in systematic assessment, rapid bleeding control, and appropriate escalation when initial measures prove inadequate. Close collaboration between emergency physicians, maxillofacial surgeons, and other specialists optimizes outcomes while minimizing complications.

Continued education and protocol development ensure that healthcare providers maintain proficiency in epistaxis management techniques and stay current with evolving treatment approaches. Quality improvement initiatives help identify best practices and optimize patient care protocols