Maxillary and Mandibular Landmarks: A Comprehensive Guide

Medi Study Go

Are you a dental student struggling to remember all those crucial maxillary and mandibular landmarks? Or maybe you're preparing for your NEET MDS exam and need a comprehensive resource that covers everything about oral anatomical structures? Look no further!

In this comprehensive guide, we'll explore everything you need to know about maxillary and mandibular anatomical landmarks - those critical structures that form the foundation of successful dental procedures and prosthetic placements. Whether you're studying for exams or refreshing your clinical knowledge, understanding these landmarks is essential for any dental professional.

Related Resources :

- Maxillary Anatomical Landmarks: Detailed Examination

- Mandibular Anatomical Landmarks: Complete Guide

- Stress-Bearing Areas of Maxillary and Mandibular Arches

- Relief Areas in Maxillary and Mandibular Prosthetics

- Clinical Applications of Maxillary and Mandibular Landmarks

Introduction

Let's face it – when I was in dental school, memorizing all the anatomical landmarks of maxillary and mandibular arches felt like learning a foreign language. But over my 15+ years in clinical practice and teaching, I've realized that these structures aren't just exam material – they're the secret sauce to successful treatments.

Think of these landmarks as nature's roadmap to the oral cavity. Just like how you'd use landmarks to navigate a city, dentists use these anatomical features to place dentures, design prosthetics, and perform various procedures. Missing these landmarks is like trying to drive without a GPS in an unfamiliar city – you'll likely end up somewhere, but probably not where you intended!

The maxillary and mandibular landmarks aren't just academic concepts. They're living, functional structures that directly impact patient outcomes. And believe me, after fitting hundreds of dentures, I can tell you that respecting these landmarks makes the difference between a patient who returns with complaints and one who refers their entire family to your practice.

Understanding Maxillary Landmarks

Primary Maxillary Landmarks

The maxillary arch contains several critical landmarks that every dental professional should know intimately. These structures form the foundation for proper denture placement and function.

Labial Vestibule and Frenum

The labial vestibule is that space between the teeth/ridge and lips that houses the labial flange of dentures. It's defined by the alveolar ridge internally and the lips externally, creating a pocket that's essential for denture retention.

Right in the middle, you'll find the labial frenum – a mucous membrane fold in the midline with no muscular attachments. But don't let its simplicity fool you! It requires careful accommodation with a notch in the denture to prevent dislodgement during function.

In my clinical experience, improper handling of the labial frenum is one of the top reasons patients complain about anterior denture discomfort. Getting this right is crucial for patient comfort and denture stability.

Buccal Frenum and Vestibule

Moving laterally, we encounter the buccal frenum, which separates the labial and buccal vestibules. Unlike its labial counterpart, this structure contains muscle attachments from:

- Levator angulii oris

- Orbicularis oris

- Buccinator

The buccal vestibule extends from the buccal frenum to the hamular notch and houses the buccal flange of the denture. Its extent can be obscured by the coronoid process, making it necessary to examine with the mouth nearly closed.

One challenging aspect of impression-taking that I've encountered repeatedly is that the buccal vestibule's size varies with buccinator muscle contraction, mandibular position, and the amount of bone lost from the maxilla. This requires careful assessment during the clinical examination.

Posterior Palatal Seal

Ask any prosthodontist about exam favorites, and the posterior palatal seal will likely top the list. This soft tissue area at the junction of the hard and soft palates is crucial for denture retention.

The posterior palatal seal is identified between the anterior vibrating line and the posterior vibrating line:

- The anterior vibrating line marks the junction of the attached tissues overlying the hard palate and the movable tissues of the immediately adjacent soft palate

- The posterior vibrating line marks the distal extension of the maxillary denture

When teaching students about complete dentures, I always emphasize that a well-established posterior palatal seal is often the difference between a denture that stays in place and one that drops during function.

Secondary Maxillary Landmarks

Beyond the primary structures, several secondary landmarks deserve attention due to their clinical significance.

Fovea Palatini

The fovea palatini are mucous gland ductal openings on either side of the midline. They serve as a reliable guide for posterior denture extent and are always located in the soft tissue.

I remember a case where a student extended a denture too far posteriorly, causing gagging and discomfort. When we reassessed, the denture extended well beyond the fovea palatini – a clear indication that proper landmark identification would have prevented this issue.

Hamular Notch

The hamular notch is a depression between the maxillary tuberosity and pterygoid hamulus. It forms the distal limit of the buccal vestibule and contains thick submucosa made of loose areolar tissue.

Clinically, it can be palpated with a mouth mirror or T-shaped burnisher. The tensor veli palatini muscle runs through this notch and ends in an aponeurosis with the contralateral muscle.

Maxillary Tuberosity

The maxillary tuberosity consists of dense fibrous connective tissues with minimal compressibility. It provides considerable support to the denture and is a primary stress-bearing area.

I've seen cases where overlooking the proper extension around the tuberosity led to denture instability. This landmark isn't just academic – it's functionally critical for prosthetic success.

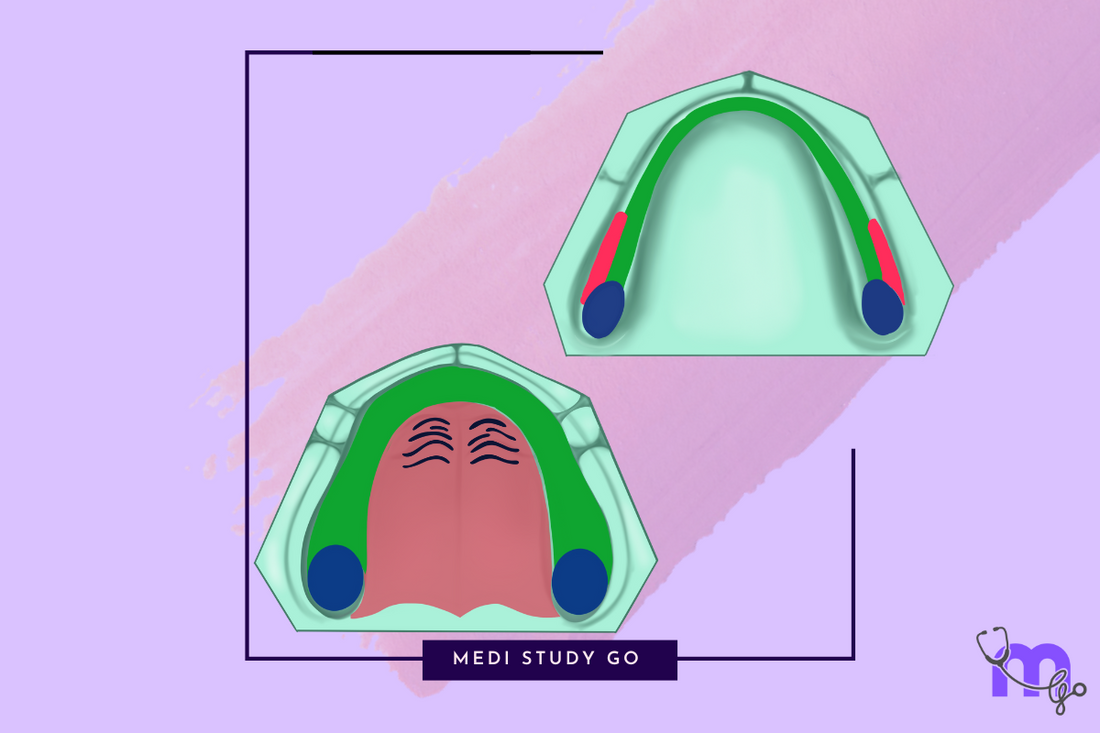

Exploring Mandibular Landmarks

Compared to their maxillary counterparts, mandibular landmarks often present greater challenges due to the dynamic nature of the mandible and the influence of tongue movement and muscle attachments.

Primary Mandibular Landmarks

Labial and Buccal Vestibules

The mandibular labial vestibule is limited by the orbicularis oris and incisive labii inferioris muscles. The labial frenum contains fibrous connective tissues that attach to the orbicularis oris.

Moving laterally, the buccal frenum overlies the depressor anguli oris and requires clearance in the denture. What's interesting is how it connects as a continuous band through the modiolus and corner of the mouth to the buccal frenum in the maxilla – truly demonstrating the interconnected nature of oral structures.

Retromolar Pad

The retromolar pad is a crucial landmark for mandibular dentures. It's composed of thin epithelium, loose areolar tissue, and various muscle fibers. The denture base should extend up to 2/3 of the retromolar pad to form the posterior seal.

I always tell students that the retromolar pad is like nature's "stop sign" for denture extension. Extend too little, and you lose stability; extend too far, and you create discomfort and functional problems.

The contents of the retromolar pad include glandular tissue, loose areolar tissue, pterygomandibular raphe, buccinator, tendon of the temporalis, and superior constrictor.

Alveololingual Sulcus

The alveololingual sulcus is the space between the residual ridge and the tongue, extending from the lingual frenum anteriorly to the retromylohyoid curtain. It accommodates the lingual flange and is heavily influenced by tongue and mylohyoid muscle movements.

This sulcus is divided into three distinct regions:

- Anterior portion (Premylohyoid area) - From lingual frenum to mylohyoid ridge

- Middle portion (Mylohyoid area) - From the premylohyoid fossa to the distal end of the mylohyoid region

- Posterior portion (Retromylohyoid area) - From the mylohyoid ridge end to the retromylohyoid curtain

Proper recording of this area gives the typical S-form of the lingual flange in mandibular dentures.

Secondary Mandibular Landmarks

Lingual Frenum

The lingual frenum is the anterior tongue attachment, overlying the genioglossus muscle. It requires accommodation by a notch in the mandibular denture to prevent displacement during tongue movement.

A clinical pearl I've learned: when patients complain about anterior mandibular denture loosening during speech, the first place to check is the lingual frenum accommodation.

Masseteric Notch

Located at the distobuccal area of the lower buccal vestibule, the masseteric notch is formed by the pulling effect of the masseter on the buccinator muscle. It accommodates anterior fibers of masseter and is influenced by buccinator activity.

Buccal Shelf

The buccal shelf is the area between the mandibular buccal frenum and the anterior ridge of the masseter muscle. It's covered by cortical bone and sits at a right angle to the occlusal plane, offering excellent resistance to vertical occlusal forces.

This structure is considered a primary stress-bearing area with well-defined boundaries:

- Medially - Crest of residual ridge

- Anteriorly - Buccal frenum

- Laterally - External oblique ridge

- Distally - Retromolar pad

In my practice, I've found that properly utilizing the buccal shelf is often the key to stable mandibular dentures, especially in cases with significant ridge resorption.

Clinical Significance in Prosthodontics

Understanding maxillary and mandibular landmarks isn't just about passing your NEET MDS exam – it's about delivering excellent patient care. These landmarks guide critical clinical decisions in prosthodontics.

Denture Extension and Design

The proper identification and recording of oral landmarks directly influence:

- The extent of denture bases

- The design of flanges

- The accommodation of frenal attachments

- The establishment of posterior seals

In complete denture prosthodontics, respecting these landmarks can mean the difference between a denture that functions properly and one that causes persistent discomfort and instability.

Stress Distribution

Not all oral tissues can bear the same amount of occlusal stress. This is where understanding stress-bearing areas becomes essential.

Maxillary Stress-Bearing Areas

Primary stress-bearing areas in the maxilla include:

- Postero-lateral slopes of hard palate

- Maxillary tuberosity

- Crest of residual alveolar ridge (with limitations)

Secondary stress-bearing areas include:

- Rugae (which resist forward movement due to their angle to the residual ridge)

- Lateral walls of the ridges (which give stability against lateral displacement)

Mandibular Stress-Bearing Areas

In the mandible, the buccal shelf serves as the primary stress-bearing area due to its cortical bone coverage and right-angle relationship to occlusal forces.

The residual alveolar ridge is considered a secondary stress-bearing area because edentulous mandibles are often extremely flat, sharp, thin, or cancellous after the loss of the cortical layer of bone.

Stress-Bearing Areas and Their Importance

Successful prosthetic treatment depends on distributing forces properly across oral tissues. This is where the concept of stress-bearing areas becomes crucial.

Maxillary Primary Stress-Bearing Areas

The postero-lateral slopes of the hard palate provide considerable surface area and support for dentures. Their bone trabecular pattern runs perpendicular to the direction of force, making them capable of withstanding tremendous pressure.

The maxillary tuberosity, with its dense fibrous connective tissues and minimal compressibility, also provides significant support to maxillary dentures.

Mandibular Primary Stress-Bearing Areas

Unlike the maxilla, the mandible has fewer primary stress-bearing areas, making mandibular denture stability more challenging. The buccal shelf stands out as the most reliable support structure, offering excellent resistance to vertical occlusal forces.

Consequences of Improper Stress Distribution

When dentures don't properly distribute force across appropriate stress-bearing areas, patients may experience:

- Accelerated bone resorption

- Chronic tissue irritation and soreness

- Denture instability

- Impaired function

I recall a patient who came to me after years of uncomfortable denture wear. Examination revealed that her previous dentures placed excessive pressure on non-stress-bearing areas, leading to significant bone loss and chronic discomfort. Redesigning her dentures with proper stress distribution principles resulted in immediate improvement in comfort and function.

Relief Areas That Require Special Attention

Just as important as knowing where to place pressure is understanding where to avoid it. Relief areas are structures that cannot tolerate significant pressure and require special accommodation in prosthetic design.

Maxillary Relief Areas

Key structures requiring relief in maxillary dentures include:

- Incisive papilla - Covers nasopalatine vessels and may require relief to avoid pressure on nerves and vessels

- Midpalatine suture - Has thin submucosa making the mucosa non-resilient

- Torus palatinus - A bony enlargement in the middle of the palate that requires relief or surgical excision

- Undercuts and sharp bony prominences

- Zygomatic process

- Sharp spiny spicules

- Cuspid eminence

Mandibular Relief Areas

In the mandible, structures requiring relief include:

- Mental foramen - Relief is provided to avoid compression of mental nerves and vessels

- Genial tubercle - May need relief, especially when prominent in cases with severe resorption

- Torus mandibularis - A bony prominence that may require surgical removal or relief

- Mylohyoid ridge - May require relief if prominently projecting

Properly identifying and accommodating these relief areas is essential for patient comfort and denture success. I've seen numerous cases where overlooking a single relief area led to persistent patient complaints that were easily resolved once identified and addressed.

NEET MDS Preparation: Key Concepts to Master

For students preparing for the NEET MDS examination, understanding maxillary and mandibular landmarks is not just about memorization – it's about clinical application and problem-solving.

High-Yield Topics for NEET MDS

Based on my analysis of previous year question papers, these topics frequently appear in NEET examinations:

- Posterior Palatal Seal - Understanding its location, function, and techniques for establishing an effective seal

- Stress-Bearing Areas - Differentiating between primary and secondary stress-bearing areas

- Fovea Palatini - Their significance as a guide for posterior denture extension

- Retromolar Pad - Its composition and role in mandibular denture extension

- Buccal Shelf - Its boundaries and importance as a primary stress-bearing area

Common NEET Question Formats

Questions on maxillary and mandibular landmarks typically appear in these formats:

- Match-the-following questions linking landmarks to their descriptions

- Case-based scenarios requiring identification of relevant landmarks

- Multiple-choice questions about the clinical significance of specific landmarks

Study Strategies for NEET Success

Beyond memorizing facts, successful NEET preparation requires:

- Visual learning - Study diagrams and develop mental images of landmark locations

- Clinical correlation - Understand the practical implications of each landmark

- Regular revision - Use flashcard techniques and revision tools for NEET to reinforce learning

- Practice questions - Work through NEET PYQs to familiarize yourself with question patterns

Study Tips and Techniques

Mastering the complex world of oral anatomy requires effective study strategies. Here are approaches that have helped my students succeed:

Effective Revision Strategies

- Create visual mnemonics - Associate landmarks with familiar objects or stories to enhance recall

- Use the "teach-back" method - Explain concepts to peers to identify knowledge gaps

- Draw and label diagrams - The physical act of drawing reinforces spatial relationships between structures

- **Use flashcard applications for NEET - Digital flashcards can make revision more efficient and accessible

Recommended Resources

For comprehensive preparation, consider these resources:

- NEET preparation books focusing on dental anatomy and prosthodontics

- NEET previous year question papers to understand examination patterns

- NEET mock tests to assess your readiness

- NEET revision tools that emphasize high-yield concepts

Last-Minute Revision Tips

As exam day approaches, focus on:

- Reviewing key landmark relationships rather than minute details

- Practicing quick sketches of maxillary and mandibular arches with landmarks

- Reviewing clinical applications of landmark knowledge

- Using last-minute revision aids to reinforce critical concepts

Remember, understanding the "why" behind each landmark's importance is more valuable than rote memorization. This conceptual understanding will serve you both in examinations and in clinical practice.

Frequently Asked Questions

What are the most important maxillary landmarks for denture fabrication?

The most critical maxillary landmarks for denture fabrication include the posterior palatal seal, maxillary tuberosity, and postero-lateral slopes of the hard palate. These structures provide primary support and retention for maxillary dentures. The posterior palatal seal, in particular, creates an effective seal that enhances denture retention through atmospheric pressure.

How do mandibular landmarks differ from maxillary landmarks?

Mandibular landmarks differ from maxillary landmarks in several ways:

- They are more influenced by muscle attachments and movement

- The mandible has fewer primary stress-bearing areas than the maxilla

- Mandibular landmarks must accommodate greater functional movement

- Relief areas are more critical in mandibular prosthetics due to the presence of important neurovascular structures like the mental foramen

Why is the retromolar pad significant in mandibular denture design?

The retromolar pad is crucial because it:

- Forms the posterior seal of the mandibular denture

- Provides a reliable landmark for determining the posterior extension of the denture base

- Contains various tissues that influence denture stability

- Helps establish proper occlusal plane height

The denture base should extend to cover approximately 2/3 of the retromolar pad for optimal results.

How do stress-bearing areas impact denture design?

Stress-bearing areas directly influence:

- The thickness of denture bases in specific regions

- The processing techniques used during denture fabrication

- The selective pressure applied during impression-taking

- The design of occlusal schemes to distribute forces appropriately

Proper utilization of stress-bearing areas leads to more comfortable, stable, and durable prosthetics.

What are common relief areas in maxillary dentures?

Common relief areas in maxillary dentures include:

- Incisive papilla

- Midpalatine suture

- Torus palatinus (if present)

- Prominent rugae

- Sharp bony prominences and undercuts

These areas require relief to prevent tissue irritation, pain, and denture instability.

How can I remember all the landmarks for my NEET MDS exam?

Rather than memorizing landmarks in isolation, try:

- Studying them in functional groups (e.g., all stress-bearing areas together)

- Creating clinical scenarios that highlight their importance

- Using flashcard techniques for study

- Regularly testing yourself with NEET mock tests

- Reviewing NEET previous year question papers to familiarize yourself with common questions

What is the significance of the buccal shelf in mandibular dentures?

The buccal shelf is significant because:

- It's covered by cortical bone, making it resistant to resorption

- It sits at a right angle to the occlusal plane, efficiently distributing vertical forces

- It provides excellent resistance to vertical occlusal forces

- It remains relatively stable even when the alveolar ridge resorbs significantly

For these reasons, the buccal shelf is considered the primary stress-bearing area for mandibular dentures.

Conclusion

Understanding maxillary and mandibular landmarks is foundational to successful dental practice, particularly in prosthodontics. These anatomical features aren't just academic concepts – they're practical guides that inform clinical decisions and directly impact patient outcomes.

For students preparing for the NEET MDS examination, mastering these landmarks requires both theoretical knowledge and clinical application. Using effective study strategies, focusing on high-yield topics, and regularly practicing with NEET PYQs and NEET mock tests can help you succeed.

Remember that landmark identification is a skill that improves with practice. The more you engage with these concepts – whether through study, clinical observation, or hands-on practice – the more intuitive they become.

Whether you're a dental student just beginning your journey or an experienced clinician refreshing your knowledge, I hope this comprehensive guide to maxillary and mandibular anatomical landmarks serves as a valuable resource in your professional development.