Mandibular Anatomical Landmarks: Complete Guide

Medi Study Go

Mastering the anatomical landmarks of mandibular arch is essential for successful dental procedures and exam success. This comprehensive guide explores the critical structures every dental professional should know.

When it comes to dental prosthetics and oral surgery, understanding mandibular landmarks can make or break your clinical outcomes. As a dental educator with over 15 years of experience, I've seen firsthand how this knowledge transforms student performance on exams like NEET MDS and enhances clinical practice.

For a complete understanding of oral anatomical landmarks, be sure to check out our related articles:

- Maxillary and Mandibular Landmarks: A Comprehensive Guide

- Maxillary Anatomical Landmarks: Detailed Examination

- Stress-Bearing Areas of Maxillary and Mandibular Arches

- Relief Areas in Maxillary and Mandibular Prosthetics

- Clinical Applications of Maxillary and Mandibular Landmarks

Introduction to Mandibular Landmarks

Let's face it – the mandible presents unique challenges that you won't encounter in the maxilla. Its dynamic nature, influenced by powerful muscles and constant movement, means that understanding its landmarks isn't just academic – it's practical necessity.

I still remember my first complete denture patient during residency. Despite following textbook procedures, the mandibular denture lacked stability. My mentor pointed out that I'd failed to properly utilize the retromolar pad and buccal shelf – a lesson in mandibular landmarks I've never forgotten.

In this guide, we'll explore each critical mandibular anatomical landmark and its clinical significance, with special attention to their importance for prosthetic dentistry and NEET MDS preparation.

Mandibular Limiting Areas

The mandible features several structures that influence denture extension and design. These limiting areas must be properly accommodated for successful prosthetic outcomes.

Labial Vestibule and Frenum

The mandibular labial vestibule is limited by the orbicularis oris and incisive labii inferioris muscles. Unlike its maxillary counterpart, the mandibular vestibule is influenced by more powerful muscle attachments.

The labial frenum contains a band of fibrous connective tissues that helps attach orbicularis oris. This structure:

- Requires accommodation by a notch in the denture

- May limit anterior denture extension if not properly recorded

- Can displace a denture during function if not adequately relieved

In my clinical experience, inadequate accommodation of the labial frenum frequently leads to anterior denture instability, particularly during speech.

Buccal Frenum and Vestibule

Moving laterally, we encounter the buccal frenum, which:

- Overlies the depressor anguli oris

- Moves vertically and horizontally during function

- Requires clearance in the denture

- Connects as a continuous band through the modiolus and corner of the mouth to the buccal frenum in the maxilla

The buccal vestibule contains several anatomical divisions with distinct characteristics. Understanding these regions is essential for proper denture extension:

-

Anterior portion (from buccal frenum to anterior border of masseter)

- Influenced by buccinator and facial expression muscles

- Relatively stable during most functions

-

Middle portion (overlying the masseter muscle)

- Subject to significant movement during mastication

- Forms the masseteric notch at its distal aspect

-

Posterior portion (retromolar region)

- Contains the retromolar pad

- Critical for denture stability and posterior seal

The masseteric notch is located at the distobuccal area of the lower buccal vestibule. It's formed by the pulling effect of the masseter on the buccinator muscle and accommodates anterior fibers of the masseter.

This notch is a key exam favorite for NEET MDS and represents an important clinical landmark for denture extension.

Lingual Frenum and Alveololingual Sulcus

The lingual frenum is the anterior tongue attachment, overlying the genioglossus muscle. It requires accommodation by a notch in the mandibular denture to prevent displacement during tongue movement.

The alveololingual sulcus is the space between the residual ridge and the tongue, extending from the lingual frenum anteriorly to the retromylohyoid curtain. This space:

- Accommodates the lingual flange

- Is influenced by tongue and mylohyoid muscle movements

- Has varying depths and configurations throughout its extent

- Requires careful recording for optimal denture stability

The sulcus is divided into three distinct regions:

- Anterior portion (Premylohyoid area) - From lingual frenum to mylohyoid ridge

- Middle portion (Mylohyoid area) - From the premylohyoid fossa to the distal end of the mylohyoid region

- Posterior portion (Retromylohyoid area) - From the mylohyoid ridge end to the retromylohyoid curtain

Proper recording of this area gives the typical S-form of the lingual flange in mandibular dentures.

I recall a challenging case where a patient complained of persistent mandibular denture dislodgment during speech. After careful examination, I discovered inadequate extension in the alveololingual sulcus. Correcting this extension dramatically improved denture stability.

Retromolar Pad: The Critical Posterior Landmark

The retromolar pad is arguably the most important posterior landmark for mandibular dentures. This structure:

- Is composed of thin epithelium, loose areolar tissue, and various muscle fibers

- Forms the posterior seal of the mandibular denture

- Contains glandular tissue, loose areolar tissue, pterygomandibular raphe, buccinator, tendon of the temporalis, and superior constrictor

For optimal denture design, the denture base should extend to cover approximately 2/3 of the retromolar pad. This extension:

- Enhances posterior stability

- Provides a posterior seal

- Helps establish proper occlusal plane height

- Contributes to overall denture retention

In my teaching experience, I've found that proper utilization of the retromolar pad is one of the most important factors in successful mandibular denture stability.

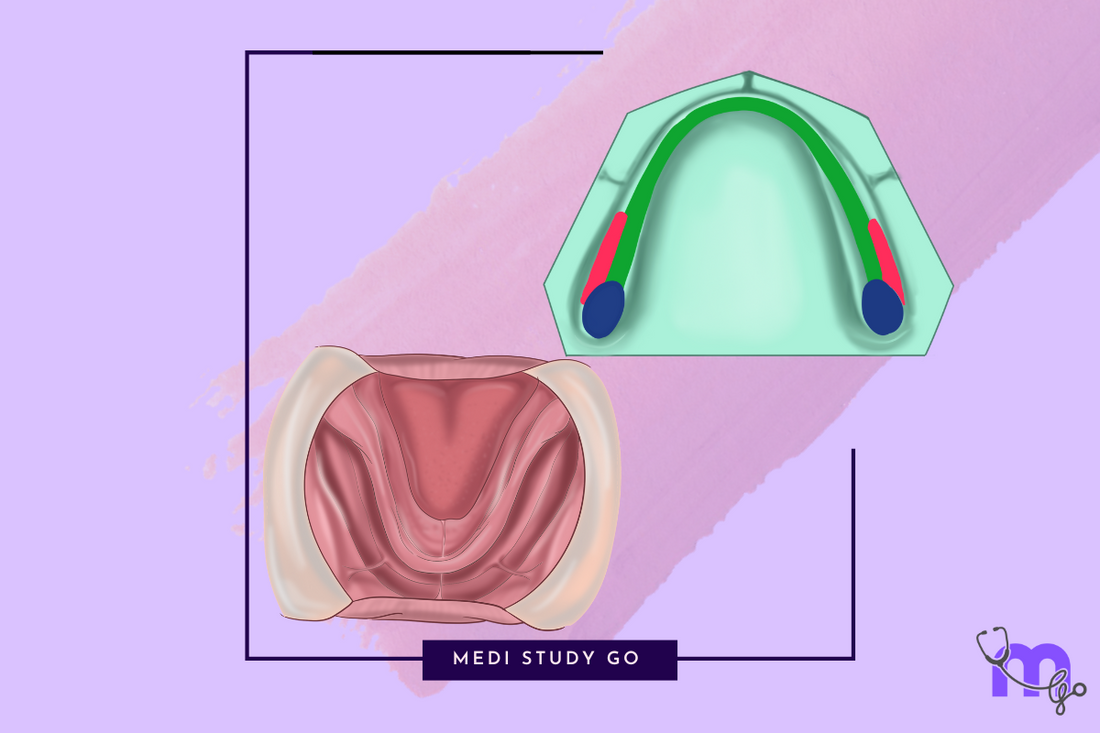

Stress-Bearing Areas of the Mandible

Understanding which mandibular structures can bear occlusal forces is crucial for prosthetic success. Unlike the maxilla, the mandible has fewer primary stress-bearing areas, making their identification and utilization even more critical.

Primary Stress-Bearing Area: Buccal Shelf

The buccal shelf is the area between the mandibular buccal frenum and the anterior ridge of the masseter muscle. This structure:

- Is covered by cortical bone

- Sits at a right angle to the occlusal plane

- Offers excellent resistance to vertical occlusal forces

- Has well-defined boundaries:

- Medially - Crest of residual ridge

- Anteriorly - Buccal frenum

- Laterally - External oblique ridge

- Distally - Retromolar pad

The buccal shelf is considered the primary stress-bearing area for mandibular dentures due to its cortical bone coverage and biomechanical advantages.

A clinical pearl I share with students: When patients present with failed mandibular dentures, inadequate utilization of the buccal shelf is often the primary culprit. Redesigning the denture to maximize support from this area frequently resolves instability issues.

Secondary Stress-Bearing Area: Residual Alveolar Ridge

The residual alveolar ridge serves as a secondary stress-bearing area, though with significant limitations. Edentulous mandibles are often:

- Extremely flat

- Sharp or thin

- Composed of cancellous bone rather than cortical bone

- Containing large nutrient canals

These characteristics result from the loss of the cortical layer of bone following tooth extraction, making the ridge less suitable for primary stress-bearing.

Nevertheless, the ridge contributes to denture support and stability when properly utilized in conjunction with the primary stress-bearing area.

Relief Areas in the Mandible

Some mandibular structures cannot tolerate significant pressure and require relief in prosthetic design. Proper identification and accommodation of these areas are essential for patient comfort and denture success.

Mental Foramen

The mental foramen transmits the mental nerve and vessels. When providing relief for this structure:

- Identify its location, which can be half way between the crest of ridge and inferior border of mandible near the premolar region

- Note that its shape and inclination vary between individuals

- Create adequate relief to avoid compression of mental nerves and vessels, which would cause pain and paresthesia

In cases with significant ridge resorption, the mental foramen may be located near or at the crest of the ridge, making its identification and relief particularly important.

Genial Tubercle

The genial tubercle may require relief, especially when prominent in cases with severe resorption. This structure:

- Serves as the attachment for genioglossus and geniohyoid muscles

- Can become more prominent as surrounding bone resorbs

- May interfere with denture stability if not properly accommodated

Torus Mandibularis

When present, a torus mandibularis (bony prominence on the lingual aspect of the mandible) requires:

- Surgical removal if large enough to interfere with denture design

- Relief in the denture if small or if surgery is contraindicated

- Special impression techniques to accurately record its extent

The decision between surgical removal and prosthetic accommodation depends on the size, location, and individual patient factors.

Mylohyoid Ridge

The mylohyoid ridge may require relief for prominent projections. This structure:

- Varies in shape and inclination between individuals

- Can become more pronounced following ridge resorption

- May interfere with denture extension if not properly managed

In extreme cases, surgical recontouring of a sharp mylohyoid ridge may be necessary before successful denture fabrication is possible.

Clinical Assessment of Mandibular Landmarks

Theoretical knowledge must be paired with practical identification skills. Based on my clinical experience, here are effective techniques for identifying mandibular landmarks:

Visual Examination

Begin with thorough visual inspection, noting:

- Ridge height, width, and contour

- Vestibular depth and configuration

- Frenal attachments and their location

- Visible tori or bony prominences

- Retromolar pad size and configuration

- Tongue size and position (which influences lingual flange design)

Palpation Techniques

Palpation provides critical information about:

- Bone density and ridge resilience

- Mylohyoid ridge location and prominence

- Mental foramen position

- Buccal shelf extent and cortical coverage

- Retromolar pad composition and resilience

I teach students to use firm but gentle pressure during palpation, particularly when assessing the buccal shelf and retromolar pad, which are crucial for successful mandibular dentures.

Functional Movement Assessment

Some landmarks are best identified during function:

- Ask the patient to extend their tongue to visualize the lingual frenum

- Request cheek movements to observe vestibular depth changes

- Have the patient close partially to assess masseteric influence on the buccal vestibule

These dynamic assessments reveal how tissues behave during function – essential knowledge for prosthetic design.

Impression Techniques for Mandibular Landmarks

Different regions of the mandible require specific impression approaches for optimal results:

Selective Pressure Technique

This approach distributes pressure according to tissue resilience and stress-bearing capacity:

- Maximal appropriate pressure on the buccal shelf and retromolar pad

- Moderate pressure on secondary stress-bearing areas

- Minimal pressure on relief areas like the mental foramen

Border Molding Considerations

Effective border molding requires understanding muscle dynamics:

- Lateral border molding captures buccinator influence

- Anterior border molding records labial muscle movements

- Lingual border molding captures tongue function

- Posterior border molding records retromylohyoid curtain movement

I've found that taking time to properly record these functional borders significantly enhances denture stability and patient comfort.

Special Considerations for Challenging Anatomies

Some anatomical variations require modified approaches:

- Highly resorbed ridges may require special impression materials or techniques

- Knife-edge ridges benefit from mucostatic impression approaches

- Flabby ridge tissue may require selective pressure techniques

Recognizing these variations and adapting impression techniques accordingly is the mark of an experienced clinician.

Importance for NEET MDS Examination

For students preparing for NEET MDS, mandibular landmarks represent high-yield examination topics. Based on NEET previous year question papers, focus on:

Commonly Tested Concepts

- Buccal shelf - Its boundaries, importance as a primary stress-bearing area, and anatomical characteristics

- Retromolar pad - Its composition, role in denture extension, and relationship to posterior seal

- Alveololingual sulcus divisions - The three distinct regions and their clinical significance

- Masseteric notch - Its formation and accommodation in prosthetic design

- Mental foramen - Location variations and clinical importance

Application-Based Questions

NEET exams frequently include scenario-based questions such as:

- Identifying the appropriate extension of a mandibular denture based on anatomical landmarks

- Determining relief requirements for specific structures

- Selecting impression techniques for challenging mandibular anatomies

Revision Strategies

Effective preparation includes:

- Using NEET revision tools that emphasize high-yield mandibular landmarks

- Creating mnemonic devices for related structures (e.g., "RMP" for Retromolar Pad properties: Resilient, Muscular, Posterior seal)

- Practicing with NEET mock tests that include clinical scenarios

- Reviewing NEET PYQs to understand common question formats

Common Clinical Challenges and Solutions

Even experienced clinicians encounter challenges related to mandibular landmarks. Here are evidence-based solutions for common issues:

Highly Resorbed Ridges

When faced with significant mandibular resorption:

- Maximize utilization of the buccal shelf for primary support

- Consider neutral zone techniques to enhance stability

- Explore implant-retained overdentures when appropriate

- Extend the denture base to the functional limits while respecting anatomical landmarks

Prominent Mylohyoid Ridge

For patients with a prominent mylohyoid ridge:

- Provide adequate relief in the denture

- Consider surgical reduction if the ridge is exceptionally sharp

- Use soft liner materials in affected areas

- Design a modified lingual flange that accommodates the ridge without sacrificing extension

Flat or Atrophic Mandible

When dealing with severe mandibular atrophy:

- Focus on peripheral seal rather than primary retention

- Utilize all available stress-bearing areas, particularly the buccal shelf

- Consider tissue conditioning to improve denture-bearing surfaces

- Explore modified impression techniques that distribute forces optimally

Advanced Concepts in Mandibular Landmarks

For clinicians seeking to deepen their understanding, here are advanced considerations:

Age-Related Changes

As patients age, mandibular landmarks undergo modifications:

- Progressive ridge resorption changes the relationship between structures

- The mental foramen moves closer to the ridge crest

- The mylohyoid ridge becomes more prominent

- The vestibular depth often decreases

These changes necessitate ongoing reassessment and adaptation of prosthetic designs.

Gender-Based Variations

Research indicates gender differences in mandibular anatomy:

- Males typically have more prominent muscle attachments

- Female patients often show different patterns of bone resorption

- The angle of the mandible tends to differ between genders

These variations should inform clinical assessment and treatment planning.

Radiographic Evaluation

While direct clinical examination is primary, radiographic assessment provides valuable information about:

- Mental foramen location and size

- Bone density in stress-bearing areas

- Presence of embedded roots or pathology

- Ridge height and width for implant considerations

Cone beam CT scans are particularly valuable for complex cases or pre-implant assessment.

Study Tips for Mastering Mandibular Landmarks

For students preparing for examinations or clinicians refreshing their knowledge:

Effective Learning Strategies

- Create anatomical correlations - Link landmarks to their functional significance

- Use multi-sensory learning - Combine visual study with tactile examination of models

- Practice identification on peers - Palpate landmarks on colleagues (where appropriate)

- Draw and label diagrams - The physical act of drawing reinforces spatial relationships

- **Utilize flashcard techniques for study - Digital flashcards make revision efficient

Recommended Resources

Beyond NEET preparation books, consider:

- Prosthodontic textbooks with clinical photos

- Anatomical atlases focusing on oral structures

- Digital resources with 3D visualizations

- NEET mock tests emphasizing clinical applications

Conclusion

Mastering mandibular anatomical landmarks requires both theoretical knowledge and practical application. These structures form the foundation of successful prosthodontic treatment and appear frequently in dental examinations.

For students preparing for NEET MDS, understanding these landmarks is essential for exam success. Utilize NEET preparation books, flashcard applications for NEET, and regular practice with NEET mock tests to reinforce your learning.

For practicing clinicians, these landmarks guide critical decisions that directly impact patient comfort and treatment outcomes. Regular reassessment of these fundamental concepts ensures continued clinical excellence.

Remember that each patient presents unique variations of these landmarks. The skill lies not just in knowing textbook descriptions but in recognizing and adapting to individual anatomical presentations.