Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation (CPR) in Dental Settings: Step-by-Step Guide for Dental Students

Medi Study Go

Related Resources:

- Comprehensive Guide to Medical Emergencies in Dentistry

- Syncope Management in Dental Clinics

-

Postural Hypotension in Dental Patients

- Tracheostomy Emergencies in Dentistry

- Anaphylaxis in Dental Practice

- Managing Acute Anginal Attacks

- Diabetic Emergencies in Dentistry

- Anticoagulant Therapy in Dental Patients

- Adrenal Insufficiency Crisis

- Hypertensive Crises in Dental Clinics

- Status Epilepticus and Status Asthmaticus

Key Takeaways:

- CPR in dental settings requires specific adaptations, including proper patient positioning in the dental chair and modified compression techniques

- Dental students must master the CAB sequence (Compressions, Airway, Breathing) and understand how to integrate dental office emergency equipment into resuscitation efforts

- Effective team coordination during dental emergencies significantly improves patient outcomes, with designated roles for staff members

- Regular CPR certification renewal and practice drills are essential for maintaining emergency readiness in dental settings

- Early recognition of cardiac arrest and immediate initiation of high-quality CPR are the most critical factors in patient survival

Introduction

Cardiac emergencies in dental settings, while relatively uncommon, represent potentially life-threatening situations requiring immediate and decisive intervention. For dental students, mastering Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation (CPR) techniques is not merely an academic requirement but a professional responsibility that can mean the difference between life and death for patients experiencing cardiac arrest. The dental chair setting presents unique challenges for performing effective CPR, including patient positioning constraints, limited space, and specialized equipment considerations. According to the American Dental Association, approximately 0.5% of dental visits involve a medical emergency, with cardiovascular events accounting for a significant proportion of these incidents.

The risk factors inherent in dental practice—patient anxiety, vasovagal reactions, medication side effects, and the potential for allergic responses—all contribute to an elevated risk of cardiac emergencies. Furthermore, many patients seeking dental care have underlying systemic conditions that predispose them to cardiovascular complications, including hypertension, coronary artery disease, and arrhythmias. An aging patient population, combined with increased use of anticoagulants and other cardiac medications, further compounds these risks. Recent studies indicate that dental professionals who maintain current CPR certification and participate in regular emergency drills respond more effectively to cardiac emergencies, significantly improving patient outcomes.

This comprehensive guide provides dental students with a step-by-step approach to performing CPR in the unique context of dental settings. We explore the specific adaptations required for the dental chair environment, the critical role of team coordination, and the integration of dental office emergency equipment into resuscitation efforts. By mastering these skills and protocols, dental students can ensure they are prepared to respond effectively to the most serious medical emergencies they may encounter in clinical practice.

Table of Contents

- Understanding Cardiac Arrest in Dental Settings

- Preparing Your Dental Office for Cardiac Emergencies

- Step-by-Step CPR Protocol for Dental Chair Settings

- Post-Resuscitation Care and Documentation

- Training, Certification, and Continuing Education Requirements

Understanding Cardiac Arrest in Dental Settings

Cardiac arrest in dental settings presents unique challenges and considerations that dental students must understand to respond effectively. The specific context of dental procedures creates distinct risk factors and recognition patterns that differ from other healthcare environments.

Risk Factors for Cardiac Events During Dental Procedures

Dental procedures can trigger cardiac events through several mechanisms. Stress and anxiety are primary contributors, with up to 75% of adults experiencing some degree of dental anxiety. This psychological stress can elevate catecholamine levels, increasing heart rate, blood pressure, and myocardial oxygen demand—potentially triggering arrhythmias or acute coronary syndromes in susceptible individuals.

Local anesthetics with vasoconstrictors introduce another layer of risk. Epinephrine in dental anesthetics, while essential for hemostasis and prolonged analgesia, can precipitate tachycardia, hypertension, and rarely, cardiac arrhythmias when administered in excessive doses or inadvertently injected intravascularly. For patients with pre-existing cardiac conditions, this presents a significant concern.

Medications commonly used in dental practice may interact with cardiac medications or directly affect cardiovascular function. Antibiotics, analgesics, and sedatives all carry potential for drug interactions that could compromise cardiac function or stability. Particularly concerning are interactions with anticoagulants, antihypertensives, and antiarrhythmics that many dental patients take chronically.

Recognizing Signs of Impending Cardiac Arrest

Early recognition of cardiac compromise is crucial for timely intervention. Prodromal symptoms that should alert dental providers include chest discomfort or pain, which may radiate to the jaw, neck, or left arm; unexpected shortness of breath, especially during minimal exertion or at rest; diaphoresis unrelated to room temperature or anxiety; unusual fatigue or weakness; and complaints of palpitations, dizziness, or lightheadedness.

Observable clinical signs requiring immediate attention include sudden changes in skin color (pallor, cyanosis, or mottling); development of irregular pulse or significant changes in heart rate; marked deviation in blood pressure from baseline; altered level of consciousness or confusion; and respiratory changes such as gasping or abnormal breathing patterns.

Monitoring equipment in modern dental offices can provide valuable objective data. Pulse oximetry showing sudden oxygen desaturation, automated blood pressure readings indicating significant hypertension or hypotension, or cardiac monitoring revealing arrhythmias all warrant immediate assessment and intervention before progression to full arrest.

How Does Cardiac Arrest in Dental Settings Differ from Other Environments?

Dental settings present unique challenges for CPR implementation. The dental chair configuration may complicate proper positioning for effective chest compressions, potentially requiring rapid transfer to a flat, firm surface or specific adaptations to technique. Limited space in treatment rooms can hamper rescuer movement and team coordination, particularly when additional emergency responders arrive.

Dental operatories typically contain equipment and instruments that may impede immediate access to the patient or limit clear circulation paths for emergency response. Awareness of spatial constraints and regular emergency drills to optimize patient access are essential considerations.

The presence of dental materials, instruments, and oral fluids introduces distinctive airway management challenges not encountered in other settings. Dental professionals must be prepared to rapidly remove materials from the oral cavity and manage potential aspiration risks prior to initiating ventilations.

Preparing Your Dental Office for Cardiac Emergencies

Effective emergency response begins with thorough preparation, ensuring that all necessary equipment is available and that the dental team is ready to respond cohesively to cardiac emergencies.

Essential Emergency Equipment for Dental Settings

Every dental office must maintain a dedicated emergency kit with components specifically selected for cardiac emergencies. This kit should include an automated external defibrillator (AED), which can increase survival rates by up to 70% when applied within 3-5 minutes of collapse. The AED should be easily accessible, regularly maintained, and all staff should be trained in its operation.

Supplemental oxygen delivery systems, including masks, nasal cannulas, and bag-valve-mask devices, are essential for supporting oxygenation during resuscitation efforts. Oxygen tanks should be routinely checked to ensure adequate supply and proper function.

Advanced airway management equipment appropriate to the training level of the dental team should be available. At minimum, this includes oropharyngeal airways in various sizes and suction equipment capable of clearing the airway rapidly and effectively.

Emergency medications must be readily available, including:

- Epinephrine (1:1000) for anaphylaxis management

- Aspirin (325mg, non-enteric coated) for suspected myocardial infarction

- Nitroglycerin tablets or spray for anginal pain

- Antihistamines for allergic reactions

- Glucose sources for hypoglycemic events

Creating an Effective Emergency Response Team

Dental offices should establish a clear emergency response protocol with designated roles for all team members. The primary responder (typically the dentist) takes charge of direct patient care, including assessment and initiation of CPR. The secondary responder assists with CPR, manages the AED, and provides supplemental oxygen.

The tertiary responder handles communication responsibilities, including activating emergency medical services, providing the office address and patient information, and guiding EMS personnel to the patient upon arrival. Additional support staff control the environment, managing other patients, clearing pathways, and retrieving emergency equipment.

Regular emergency drills, conducted at least quarterly, help ensure all team members understand their roles and can execute them efficiently under pressure. These drills should simulate various emergency scenarios, including cardiac arrest in different office locations and with different team compositions.

Pre-Treatment Assessment to Identify High-Risk Patients

Thorough medical history evaluation is the foundation of risk assessment, with particular attention to cardiovascular conditions, including previous myocardial infarction, angina, arrhythmias, heart failure, and prior cardiac surgeries. Noting current cardiac medications, including anticoagulants, antihypertensives, antiarrhythmics, and vasodilators, helps identify potential medication interactions and complications.

Vital signs monitoring should be standard for all patients, with baseline blood pressure, heart rate, and respiratory rate recorded before procedures. Significant deviations from normal ranges may warrant postponement of elective procedures or medical consultation.

Risk stratification protocols help categorize patients according to cardiac risk level, guiding treatment modifications and emergency preparedness. For high-risk patients, consider:

- Scheduling appointments during morning hours when stress levels are typically lower

- Shorter appointment durations to minimize physiological stress

- Use of supplemental oxygen during procedures

- Continuous vital signs monitoring throughout treatment

- Premedication protocols as recommended by the patient's cardiologist

- Having a dedicated team member observe the patient for signs of distress

Step-by-Step CPR Protocol for Dental Chair Settings

The unique environment of the dental operatory requires specific adaptations to standard CPR protocols to ensure effective resuscitation while maintaining safety for both patient and providers.

Initial Assessment and Activation of Emergency Response

Recognition of cardiac arrest begins with checking responsiveness by tapping the patient's shoulders and asking loudly, "Are you okay?" Simultaneously assess for normal breathing, noting that gasping is not considered normal breathing and may indicate cardiac arrest. If the patient is unresponsive and not breathing normally, immediately call for help and activate your office emergency response system.

Delegate a specific team member to call emergency medical services (911) and clearly communicate:

- The nature of the emergency (suspected cardiac arrest)

- Office location and suite number

- Patient's age and gender

- Current status and interventions being performed

While maintaining focus on the patient, ensure retrieval of the emergency kit and AED by clearly designating this task to a team member: "Maria, bring the emergency kit and AED now."

Performing CPR in the Dental Chair vs. Floor

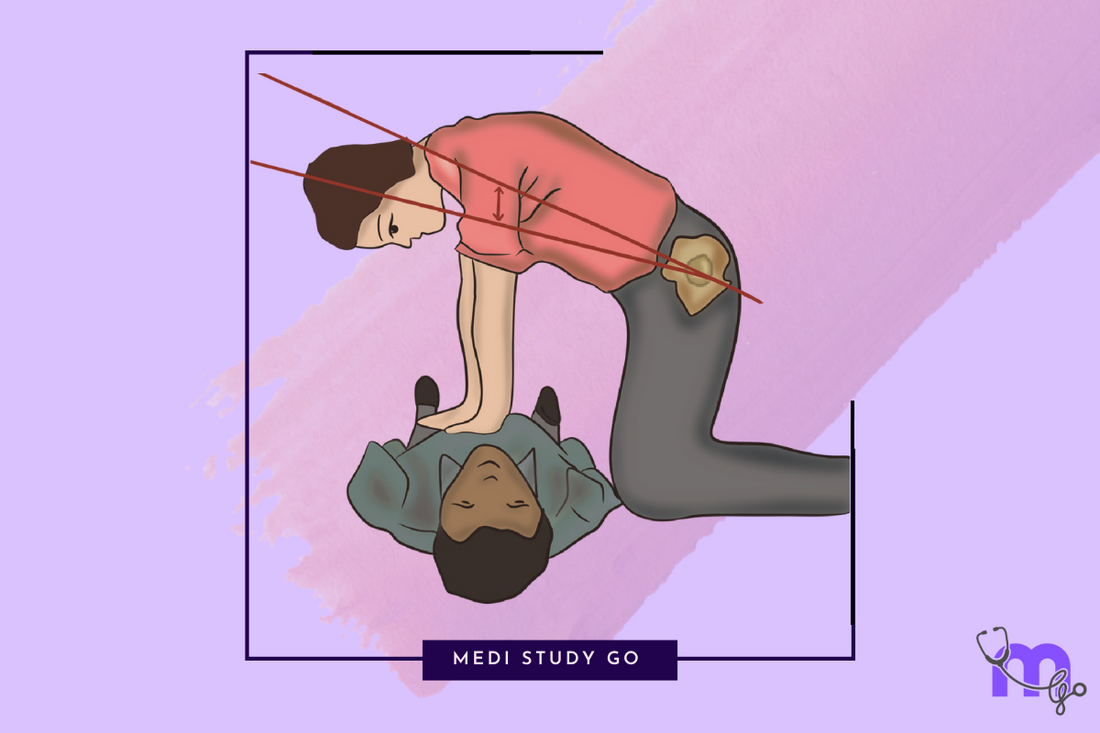

When cardiac arrest occurs in a dental chair, assessment of the chair position is crucial. If the chair can be quickly lowered to a flat position with firm back support, perform CPR in the chair initially while preparing for potential relocation. Position yourself at the head of the chair for compressions, ensuring proper body alignment for effective force delivery.

If the dental chair cannot provide adequate support for effective compressions, rapid transfer to the floor becomes necessary. This requires:

- Clear communication: "On my count, we'll move the patient to the floor."

- Coordinated movement with at least 3-4 team members

- Protection of the patient's head and neck during transfer

- Immediate resumption of compressions once positioned on a hard surface

The CAB Sequence: Compressions, Airway, Breathing

Modern CPR prioritizes chest compressions over airway management, following the CAB (Compressions, Airway, Breathing) sequence rather than the earlier ABC approach. Begin compressions immediately upon recognizing cardiac arrest, positioning hands in the center of the chest, between the nipples.

For effective compressions:

- Push hard and fast at a rate of 100-120 compressions per minute

- Depress the chest at least 2 inches (5 cm) in adults

- Allow complete chest recoil between compressions

- Minimize interruptions to maintain coronary and cerebral perfusion

Airway management follows initial compressions, with particular attention to dental materials that may be present. Quickly remove any instruments, materials, or devices from the oral cavity and perform a head-tilt, chin-lift maneuver to open the airway. In cases of suspected cervical injury, use a jaw-thrust without head extension.

For breathing support, utilize a pocket mask with one-way valve or bag-valve-mask device with supplemental oxygen when available. Deliver two breaths after every 30 compressions, with each breath taking approximately 1 second and producing visible chest rise.

Using the AED in Dental Settings

Early defibrillation significantly improves survival rates in cardiac arrest. Apply the AED as soon as it arrives, minimizing interruptions to chest compressions. Position electrode pads according to package instructions, typically one pad to the right of the sternum below the clavicle and the other on the left lateral chest wall.

Clear all team members from contact with the patient during analysis by stating loudly, "Stand clear, analyzing rhythm." If a shock is advised, ensure all personnel are clear of the patient and dental chair, announcing, "Everyone clear, delivering shock," before pressing the shock button.

Resume CPR immediately after shock delivery or if no shock is advised, beginning with compressions. Continue the CPR cycle with minimal interruptions, allowing the AED to reanalyze rhythm every 2 minutes.

What Drugs Are Essential in a Dental Emergency Kit for Cardiac Patients?

A comprehensive dental emergency kit for cardiac patients must include medications that can address various aspects of cardiac emergencies. Vasodilators like nitroglycerin (0.4mg sublingual tablets or spray) provide rapid relief for anginal symptoms by dilating coronary vessels and reducing myocardial oxygen demand. For suspected myocardial infarction, non-enteric coated aspirin (325mg) inhibits platelet aggregation and can reduce mortality when administered promptly.

Epinephrine (1:1000 solution in pre-filled syringes or ampules) serves as the primary medication for anaphylaxis but also has critical applications in resuscitation by increasing coronary and cerebral perfusion pressure. Atropine (0.5mg ampules) may be included for managing symptomatic bradycardia until advanced medical support arrives.

Supplementary medications should include antihistamines (diphenhydramine 50mg) for allergic reactions, bronchodilators (albuterol inhaler) for bronchospasm, and glucose preparations for hypoglycemic events. Oxygen, while not a medication per se, is essential for supporting tissue oxygenation during cardiac emergencies.

Post-Resuscitation Care and Documentation

After successful resuscitation or upon EMS arrival, comprehensive care continues with focused attention on stabilization and thorough documentation of the event.

Transferring Care to Emergency Medical Services

When emergency medical services arrive, provide a concise, structured handoff using the SBAR format:

- Situation: Brief description of the emergency event

- Background: Relevant medical history and dental procedure being performed

- Assessment: Initial condition, interventions performed, and current status

- Recommendations: Share any insights about the patient's specific needs

Provide essential documentation to EMS personnel, including medical history forms, current medication list, and vital signs recorded before and during the emergency. Be prepared to share specific details about the resuscitation effort, including:

- Time of arrest and recognition

- Initial rhythm if known (from AED analysis)

- Duration of CPR and number of shocks delivered

- Medications administered with dosages and times

- Patient's response to interventions

Continue to assist EMS personnel as needed during transport preparation, ensuring all patient belongings and important documents are transferred appropriately.

Documentation and Quality Improvement

Complete comprehensive documentation of the emergency immediately while details remain fresh. Include chronological details of the event, starting with initial symptoms, time of arrest, specific interventions with timestamps, and patient responses to treatment. Document all medications administered with exact dosages, routes, times, and administration personnel.

Record all monitoring data, including vital signs, oxygen saturation readings, and any cardiac rhythm information available from the AED. Note the names and roles of all staff members involved in the resuscitation effort, as well as the time of EMS arrival and transfer of care.

Conduct a post-event debriefing with all team members within 24-48 hours to identify strengths and opportunities for improvement in the emergency response. This should be a non-punitive discussion focused on system improvements rather than individual performance.

Implement a follow-up protocol for contacting the patient or family and coordinating with the receiving hospital to understand patient outcomes and identify potential improvements to emergency protocols.

Patient Follow-Up and Continuity of Care

Establish a system for maintaining communication with the patient, family, and treating physicians following a cardiac emergency. This includes designating a specific team member as the primary contact person for the patient and family, providing clear contact information and availability.

Develop protocols for determining appropriate timing for dental treatment resumption following a cardiac event, including consultation with the patient's cardiologist and primary care provider. This may involve obtaining written clearance from medical providers and implementing modified treatment protocols.

Consider the psychological impact of cardiac events on patients and provide appropriate resources for emotional support. Many patients experience significant anxiety about returning to the dental environment after a medical emergency, and addressing these concerns compassionately is an important aspect of comprehensive care.

Training, Certification, and Continuing Education Requirements

Maintaining current knowledge and skills in CPR and emergency management is an ongoing professional responsibility for all dental professionals.

Basic Life Support (BLS) Certification for Dental Professionals

All dental students and practitioners must obtain and maintain Basic Life Support (BLS) for Healthcare Providers certification through recognized organizations such as the American Heart Association or American Red Cross. This certification typically requires renewal every two years and includes hands-on skills assessment in adult, child, and infant CPR; AED use; and relief of foreign-body airway obstruction.

Dental-specific BLS courses are increasingly available and recommended, as they address the unique challenges of performing resuscitation in dental settings. These specialized courses incorporate scenarios relevant to dental practice and provide practical strategies for implementing CPR in the dental chair environment.

Some jurisdictions require dental professionals to maintain advanced certification beyond basic BLS, such as Advanced Cardiovascular Life Support (ACLS) or Pediatric Advanced Life Support (PALS), particularly for those administering moderate sedation or working with medically complex patients.

How to Differentiate Syncope from Hypoglycemia in Dental Patients?

Distinguishing between syncope and hypoglycemia in dental settings requires careful observation of onset patterns and clinical manifestations. Syncope typically presents with a rapid onset characterized by sudden pallor, diaphoresis, and declining consciousness, often preceded by feelings of lightheadedness or visual changes. Recovery is usually spontaneous and complete within minutes once the patient is placed in a supine position with elevated legs.

Hypoglycemia, conversely, shows a more gradual onset with progressive symptoms including confusion, irritability, and hunger before potential loss of consciousness. Patients may exhibit diaphoresis, tachycardia, and anxiety that worsen over time if not addressed. The condition does not improve with positional changes alone and requires glucose administration for resolution.

Physical examination provides additional differentiating factors: syncope patients typically maintain normal muscle tone during the event and have stable vital signs during recovery, while hypoglycemic patients may exhibit altered muscle tone and have unstable vital signs until glucose levels normalize. Patient history offers crucial context—recent meals, diabetes status, and medication profile help differentiate between these conditions requiring distinct management approaches.

Incorporating Simulation Training and Regular Drills

Simulation training provides invaluable experience in managing emergencies without patient risk. Modern dental education increasingly incorporates high-fidelity simulators that can mimic cardiac arrest scenarios, allowing students to practice recognition, response, and team coordination in realistic conditions. These simulations should include scenarios specific to dental settings, such as cardiac arrest during administration of local anesthesia or in patients with known cardiac conditions.

Regular emergency drills in the clinical setting help maintain readiness and identify system issues before real emergencies occur. These drills should be conducted at least quarterly and include:

- Unannounced scenarios to test real-time response capabilities

- Rotation of roles so all team members gain experience in different aspects of emergency management

- Simulated use of actual emergency equipment, including the AED and oxygen delivery systems

- Documentation practice to ensure familiarity with emergency recordkeeping requirements

- Debriefing sessions to analyze performance and identify improvement opportunities

Peer review and case discussion forums provide opportunities to learn from actual emergency events. Establishing regular reviews of emergency cases, whether from your practice or published case reports, creates a culture of continuous improvement and reinforces the importance of emergency preparedness.

Conclusion

Mastering cardiopulmonary resuscitation in the dental setting represents a critical component of comprehensive patient care and professional responsibility. The unique challenges presented by the dental environment—including patient positioning, equipment constraints, and procedure-specific risks—require dedicated training and preparation beyond standard CPR certification. For dental students, developing these specialized skills early in their training establishes a foundation for career-long commitment to patient safety.

The evidence clearly demonstrates that outcomes from cardiac arrest in dental settings are significantly improved when the dental team can deliver high-quality CPR with minimal delays. This requires not only technical proficiency in compression techniques and AED use but also effective team coordination and clear emergency protocols tailored to the dental practice environment. Regular practice through simulation and drills ensures that these skills remain sharp and that all team members understand their roles during an emergency.

Beyond the technical aspects of resuscitation, comprehensive emergency preparedness includes thorough pre-treatment assessment, appropriate risk stratification, and modification of dental treatment plans for high-risk patients. The integration of medical and dental care through proper documentation and communication with patients' physicians further enhances safety and supports continuity of care following adverse events.

As dental students transition to independent practice, maintaining current certification and continuing education in emergency management should remain a priority throughout their careers. The professional and ethical obligation to ensure patient safety extends to all aspects of dental practice, with emergency preparedness serving as a fundamental component of the standard of care. By embracing this responsibility and committing to excellence in CPR and emergency response, dental professionals can provide their patients with confidence that they are prepared to manage even the most critical situations effectively.